Meteor (film)

| Meteor | |

|---|---|

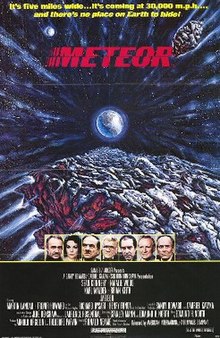

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ronald Neame |

| Screenplay by | Stanley Mann Edmund H. North |

| Story by | Edmund H. North |

| Produced by | Arnold Orgolini Theodore R. Parvin Run Run Shaw |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Paul Lohmann |

| Edited by | Carl Kress |

| Music by | Laurence Rosenthal |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures (North America) Warner Bros (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Countries | United States Hong Kong[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $16 million[2] or $15.4-17 million[3] |

| Box office | $8.4 million (domestic) or $4.2 million (US rentals)[3][4] |

Meteor is a 1979 American science fiction disaster film directed by Ronald Neame and starring Sean Connery and Natalie Wood. The film's premise, which follows a group of scientists struggling with Cold War politics after an asteroid is detected to be on a collision course with Earth, was inspired by a 1967 MIT report, Project Icarus.[5][6] The screenplay was written by Oscar winner Edmund H. North and Stanley Mann.

The international cast also includes Karl Malden, Brian Keith, Martin Landau, Trevor Howard, Joseph Campanella, Richard Dysart and Henry Fonda. The film was a box-office flop and received negative reviews,[7] but it was nonetheless nominated for the Academy Award for Best Sound.

Plot

[edit]After the asteroid Orpheus in the Asteroid Belt is hit by a comet, dozens of asteroid fragments are sent on a collision course with Earth, along with a five-mile-wide fragment that will cause an extinction-level event. While the United States government engages in political maneuvering, the smaller asteroid fragments preceding the main body wreak havoc on the planet, revealing the threat. The United States has a secret orbiting nuclear missile platform satellite named Hercules that was designed by Dr. Paul Bradley. It was intended to defend Earth against a threat like Orpheus, but instead was commandeered by the U.S. Armed Forces to become an orbiting weapon now aimed at the Soviet Union. After many calculations, it is determined that the fourteen nuclear missiles on board Hercules are not enough to stop the asteroid.

The United States has known that the Soviet Union also has a similar weapons satellite in orbit called Peter the Great, with its sixteen nuclear warheads pointed at the United States. Needing the additional firepower to stop Orpheus, the President goes on national television and reveals the existence of Hercules, explaining it was created to meet the threat that Orpheus represents. He also offers the Soviets a chance to save face by announcing that they had the same program and their own satellite weapon. To coordinate the counter-effort between the two countries, Bradley requests a Soviet scientist named Dr. Alexei Dubov.

Bradley and Harry Sherwood of NASA meet at the control center for Hercules, located beneath 195 Broadway in Lower Manhattan. Major General Adlon is the commander of the facility. Dubov and his interpreter Tatiana Donskaya arrive, and Bradley gets to work on breaking the ice between them. Since Dubov cannot admit the existence of the Soviet device, he agrees to Bradley's proposal that they work on the "theoretical application" of how a "theoretical" Soviet space platform's weapons would be coordinated with the American platform.

Meanwhile, more meteorite fragments strike Earth (one inside Siberia), and the Soviets finally agree to join in the effort. Both satellites are coordinated and turned toward the incoming large asteroid as smaller fragments continue to strike the planet, causing great damage, including a deadly avalanche in the Swiss Alps and a tsunami that devastates Hong Kong. With hours remaining until Orpheus' impact, Peter the Great's missiles are launched first as planned because of its relative position to the asteroid, with Hercules's missiles timed to be fired forty minutes later.

Immediately prior to Hercules's missiles being launched, a splinter fragment is discovered to be heading toward the command center in New York City. If the center is destroyed, Hercules will not be able to launch. With seconds to spare, Hercules receives the signal to fire from the command center and launches its missiles. The splinter impacts the city, destroying the top half of the World Trade Center twin towers in a direct hit, and creating a large crater in Central Park. Several workers inside the control center are killed when the facility is partially destroyed by the collapse of the building above, and the survivors are forced to work their way out of the control center by going through the New York subway system, which becomes a trap due to water from the East River flooding the tunnels. Meanwhile, the two flights of missiles link up into three successively larger waves. The Hercules crew reaches a crowded subway station and waits while others try to dig them out.

Eventually, the missiles reach the meteoroid. The first wave of missiles strikes the rock, causing a small explosion; the second wave follows with a larger blast, and the third wave creates an enormous explosion. When the dust clears, the asteroid appears obliterated. In New York City, the radios broadcast the good news: Orpheus is no longer a danger to Earth. Just then, the subway station occupants are rescued.

Later, at an airport, Dubov, Tatiana, Bradley and others exchange goodbyes before Dubov and Tatiana depart on a plane for the Soviet Union.

Cast

[edit]- Sean Connery as Dr. Paul Bradley

- Natalie Wood as Tatiana Donskaya

- Karl Malden as Harry Sherwood

- Brian Keith as Dr. Alexei Dubov

- Martin Landau as General Adlon

- Trevor Howard as Sir Michael Hughes

- Richard Dysart as Secretary of Defense

- Henry Fonda as The President

- Joseph Campanella as General Easton

- Bo Brundin as Rolf Manheim

- Roger Robinson as Bill Hunter

- Michael Zaslow as Sam Mason

- Bibi Besch as Helen Bradley

- Sybil Danning as Girl Skier

- Simon Cadell as BBC tv reporter

Production

[edit]Theodore R. Parvin received the idea for the story from a Saturday Review article by Isaac Asimov about a meteor hitting a major city in the United States. Parvin hired Edmund H. North to write the screenplay, and North took further inspiration from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Project Icarus. However, Ronald Neame and Sean Connery disliked both North's script and a rewrite by Steven Bach, so Stanley Mann was hired to completely re-write the screenplay. This led to a Writers Guild of America dispute over whether North should be credited as a co-writer.[8]

During the writing of North's first draft, Parvin secured financing and investment from the Shaw Brothers Studio, Warner Bros. Pictures, Nippon Herald Films and American International Pictures.[8] The film was an American International Pictures co-production with the Shaw Brothers Studio in British Hong Kong.[9] $2.7 million of the budget came from AIP.[10]

Neame cast Natalie Wood as Tatiana because she was the daughter of Russian immigrants, and she worked with George Rubinstein to perfect a Leningrad accent. Alec Guinness, Yul Brynner, Rod Steiger, Maximilian Schell, Peter Ustinov, Eli Wallach, Telly Savalas, Theodore Bikel, Richard Burton and Orson Welles were each considered for the role of Dr. Dubov. Donald Pleasence was cast for the role and filmed a few scenes as the character. However, he departed the production to work on the film Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. He was replaced by Brian Keith, who had been cast as General Adlon. Keith was replaced in that role by Martin Landau.[8] Another reason why Brian Keith was chosen to play the role of Dr. Dubov was that he could speak fluent Russian.

Principal photography took place from October 31, 1977, to January 27, 1978, mainly at MGM Studios in Culver City, California, with some location filming in Washington, D.C., St. Moritz, Switzerland, and Hong Kong.[8] The release date was scheduled for June 15, 1979, but it was pushed back to October 19 due to special effects reshoots after special effects director Frank Van der Veer was fired.

Special effects

[edit]With most of the special effects budget already expended by Van de Veer (whose work was not usable and was subsequently discarded), William Cruise and Margo Anderson were hired to reshoot as many special effects as possible with what money remained. They were also fired and replaced by Paul Kassler and Rob Balack, who were asked to complete the special effects, again with what money remained in the budget (and just two months before the film's release). To complete the film on time, Kassler and Balack reused footage from the 1978 disaster film Avalanche, filmed the Hong Kong "tidal wave" scene in Los Angeles in an improvised water tank using cardboard cutouts of buildings, and used 22-inch-long nuclear missile satellite miniatures that were far too small for effective filming.[8]

Prop designer John Zabrucky, who had previously worked only in television, provided props for the film.[11]

Music

[edit]The film was originally supposed to receive a score by John Williams, but he was forced to leave the project after delays on the film's production conflicted with his commitments to Steven Spielberg's 1941.[8]

Reception

[edit]Meteor was received poorly by critics. In her review in The New York Times, Janet Maslin called the film "standard disaster fare", adding that "the suspense is sludgy and the character development nil".[12]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 1½ stars out of 4 and wrote, "Let's face it, the bottom line on a disaster film is how special are its special effects. With 'Meteor,' the answer is not very. The big meteor in the picture, hurtling toward Earth at 30,000 miles an hour, looks like something I recently found at the bottom of my refrigerator — green bread."[13]

Variety called the acting "uniformly good", but the "principals mostly stand around waiting for the next calamity to happen ... What really matters to audiences for this kind of film, of course, is not the acting, but the visuals, and here, 'Meteor' gets good, but not great, grades."[14]

Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote that "against its own odds, it is—for what it intends to be—uninspired but competent, efficient, commercial and entertaining, with some random moments that are very nice indeed."[15]

Judith Martin of The Washington Post called it "your standard 'My God — here it comes!' job, for those that like that sort of thing".[16]

John Pym of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "As effects go, and effects rather than surprises (or any real plotline) are what the producers have banked on, Meteor looks decidedly old-fashioned and second-hand."[17]

TV Guide wrote: "An $18 million, star-studded disaster film, which in itself is a major disaster."[18]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a rating of 5% based on 19 reviews, with the site's consensus being: "Meteor is a flimsy flick with too much boring dialogue and not enough destruction. At least the pinball game is decent."[19]

Marvel Comics published a comic book adaptation of the film by writer Ralph Macchio and artists Gene Colan and Tom Palmer in Marvel Super Special #14.[20][21]

Samuel Z. Arkoff called Meteor the most difficult production ever undertaken by American International Pictures due to the high production, special effects and marketing costs. After the film flopped, the studio was forced to enter negotiations for a buyout from Filmways.[8]

Accolades

[edit]At the 52nd Academy Awards in 1980, the film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Sound (William McCaughey, Aaron Rochin, Michael J. Kohut and Jack Solomon).[22] It lost to Apocalypse Now.

Scientific basis

[edit]A voiceover at the end of the film mentions "Project Icarus", a report on the concept to use missiles to deflect an earthbound asteroid.[23] The original Project Icarus was a student project at M.I.T., in a systems engineering class led by Professor Paul Sandorff in spring 1967.[5] It examined methodologies that could deflect an Apollo asteroid named 1566 Icarus if it were found to be on a collision course with Earth. Time published an article about the research in June 1967.[24] The results of the student reports were published in a book the following year.[5][25]

See also

[edit]- Asteroid impact avoidance

- Armageddon (1998)

- Deep Impact (1998).

- Meteor (2009), a 4-hour 2-part miniseries.

- Don't Look Up (2021).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Craig, Rob (15 February 2019). American International Pictures: A Comprehensive Filmography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 255. ISBN 9781476635224. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Lee, Grant (May 29, 1978). "Buried Alive--in the Line of Duty". Los Angeles Times. p. f5.

- ^ a b Epstein, Andrew (Apr 27, 1980). "THE BIG THUDS OF 1979--FILMS THAT FLOPPED, BADLY". Los Angeles Times. p. o6.

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 300. ISBN 9780835717762. Please note figures are for rentals in US and Canada

- ^ a b c Kleiman Louis A., Project Icarus: an MIT Student Project in Systems Engineering Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine (M.I.T. Report No. 13), Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1968; reissued 1979

- ^ "MIT Course precept for movie" Archived 2011-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, The Tech, MIT, October 30, 1979

- ^ "REVIEW: "METEOR" (1979)". www.cinemaretro.com. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Meteor – History". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Jerry; Soble, Ronald L. (July 2, 1978). "'Meteor'--How a Movie Came to Be: HOW 'METEOR' BECAME A MOVIE A Movie Is Born; a Meteor Is the Star A Meteoric Idea Becomes a Movie MOVIE-MAKING". Los Angeles Times. p. a1.

- ^ Cohen, Jerry; Soble, Ronald L. (July 4, 1978). "Film Casting: Finding the 'Horse for the Course'". Los Angeles Times. pp. 1, 3, 11–14.

- ^ Gray, Andy (May 21, 2020). "Warren native imagined the future". Tribune Chronicle. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (October 19, 1979). "Screen: 'Meteor,' a Disaster Tale, Opens: Menace from the Blue". The New York Times. Retrieved July 9, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ Siskel, Gene (October 22, 1979). "Effects aren't special, so 'Meteor' falls". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 6.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Meteor". Variety. October 17, 1979. 10.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (October 19, 1979). "'Meteor': Shot at the Screen". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 22.

- ^ Martin, Judith (October 26, 1979). "'Meteor': Disasters From Many Stars". The Washington Post. Weekend, p. 31.

- ^ Pym, John (January 1980). "Meteor". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 47 (552): 9.

- ^ Meteor at TV Guide

- ^ "Meteor". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Marvel Super Special #14". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Friedt, Stephan (July 2016). "Marvel at the Movies: The House of Ideas' Hollywood Adaptations of the 1970s and 1980s". Back Issue! (89). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 62.

- ^ "The 52nd Academy Awards (1980) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ "Giant bombs on giant rockets: Project Icarus". The Space Review. July 5, 2004.

- ^ "Systems Engineering: Avoiding an Asteroid". Time. June 16, 1967. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007.

- ^ "Review:Project Icarus". 1968. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

External links

[edit]- Meteor at IMDb

- Meteor at the TCM Movie Database

- 1979 films

- 1970s science fiction action films

- 1970s disaster films

- American disaster films

- American International Pictures films

- American science fiction action films

- American space adventure films

- Fiction about the Apollo asteroids

- Cold War films

- Shaw Brothers Studio films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films adapted into comics

- Films directed by Ronald Neame

- Films set in Hong Kong

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Switzerland

- Films about impact events

- Fiction about meteoroids

- Films scored by Laurence Rosenthal

- Films with screenplays by Stanley Mann

- Comets in film

- Avalanches in film

- Films shot in Switzerland

- Films shot in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot in Hong Kong

- Films shot in Los Angeles County, California

- 1970s American films

- 1979 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction action films