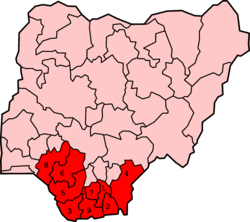

Conflict in the Niger Delta

The current conflict in the Niger Delta first arose in the early 1990s over tensions between foreign oil corporations and a number of the Niger Delta's minority ethnic groups who feel they are being exploited, particularly the Ogoni and the Ijaw. Ethnic and political unrest continued throughout the 1990s despite the return to democracy[17] and the election of the Obasanjo government in 1999. Struggle for oil wealth and environmental harm over its impacts has fueled violence between ethnic groups, causing the militarization of nearly the entire region by ethnic militia groups, Nigerian military and police forces, notably the Nigerian Mobile Police.[18] The violence has contributed to Nigeria's ongoing energy supply crisis by discouraging foreign investment in new power generation plants in the region.

From 2004 on, violence also hit the oil industry with piracy and kidnappings. In 2009, a presidential amnesty program accompanied with support and training of ex-militants proved to be a success. Thus until 2011, victims of crimes were fearful of seeking justice for crimes committed against them because of a failure to prosecute those responsible for human rights abuses.[19]

Background

[edit]Nigeria, after nearly four decades of oil production, had by the early 1980s become almost completely economically dependent on petroleum extraction, which at the time generated 25% of its GDP. This portion has since risen to 60%, as of 2008. Despite the vast wealth created by petroleum, the benefits have been slow to trickle down to the majority of the population, who since the 1960s have increasingly been forced to abandon their traditional agricultural practices. Annual production of both cash and food crops dropped significantly in the later decades of the 20th century. Cocoa production dropped by 43% for example; Nigeria was the world's largest cocoa exporter in 1960. Rubber production dropped by 29%, cotton by 65%, and groundnuts by 64%.[20] While many skilled, well-paid Nigerians have been employed by oil corporations, the majority of Nigerians and most especially the people of the Niger Delta states and the far north have become poorer since the 1960s.[21]

The Delta region has a steadily growing population estimated at more than 30 million people in 2005, and accounts for more than 23% of Nigeria's total population. The population density is also among the highest in the world, with 265 people per square kilometre, according to the Niger Delta Development Commission. This population is expanding at a rapid 3% per year and the oil capital, Port Harcourt, and other large towns are also growing quickly. Poverty and urbanization in Nigeria are growing, and official corruption is considered a fact of life. The resulting scenario is one in which urbanization does not bring accompanying economic growth to provide jobs.[20]

Some Nigerian scholars state that the Niger Delta conflict has roots in a long history of exploitation and dispossession of the region beginning during the British imperial era: first for slaves during the 17th and 18th century, later for palm oil during the 19th century, and finally for petroleum after Nigerian independence.[22] Conflict has also resulted from artificial political borders drawn during British rule that resulted in nearly 300 ethnic groups being arbitrarily consolidated into a single nation-state.[23]

Ogoni crisis

[edit]Ogoniland is a 1,050-square-kilometre (404-square-mile) region in the southeast of the Niger Delta basin. Economically viable petroleum was discovered in Ogoniland in 1957, just one year after the discovery of Nigeria's first commercial petroleum deposit. Royal Dutch Shell and Chevron Corporation set up shop there throughout the next two decades. The Ogoni people, a minority ethnic group of about half a million people who call Ogoniland home, and other ethnic groups in the region attest that during this time, the government began forcing them to abandon their land to oil companies without consultation, offering negligible compensation.

A 1979 constitutional amendment gave the federal government full ownership and rights to all Nigerian territory and also declared that eminent domain compensation for seized land would "be based on the value of the crops on the land at the time of its acquisition, not on the value of the land itself." The Nigerian government could now distribute the land to oil companies as it deemed fit, said the Human Rights Watch.[24]

The 1970s and 1980s saw government promised benefits for the Niger Delta peoples fall through and fail to materialize, with the Ogoni growing increasingly dissatisfied and their environmental, social, and economic apparatus rapidly deteriorating. The Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) was formed in 1992, spearheaded by Ogoni playwright and author Ken Saro-Wiwa, became the major organization representing the Ogoni people in their struggle for ethnic and environmental rights. Its primary targets, and at times adversaries, have been the Nigerian government and Royal Dutch Shell.

Beginning in December 1992, the conflict between the Ogoni and the oil companies escalated to a level of greater seriousness and intensity on both sides. Both parties began carrying out acts of violence and MOSOP issued an ultimatum to the oil companies (Shell, Chevron, and the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation) demanding some $10 billion in accumulated royalties, damages and compensation, and "immediate stoppage of environmental degradation", as well as negotiations for mutual agreement on all future drilling.[25]

The Ogonis threatened mass action to disrupt oil company operations if they failed to comply with MOSOP demands, and thereby shifted the focus of their actions from the unresponsive federal government to the oil companies producing in the region. The rationale for this assignment of responsibility was the benefits accrued by the oil companies from extracting the natural wealth of the Ogoni homeland, and the central government's neglectful failure to act.

The government responded by banning public gatherings and declaring disturbances to oil production acts of treason. Oil extraction from the territory slowed to a trickle of 10,000 barrels per day (1,600 m3/d) (.5% of the national total).

Military repression escalated in May 1994. On May 21, soldiers and mobile policemen appeared in most Ogoni villages. On that day, four Ogoni chiefs (all on the conservative side of a schism within MOSOP over strategy) were brutally murdered. Saro-Wiwa, head of the opposing faction, had been denied entry to Ogoniland on the day of the murders, but he was detained in connection with the killings. The occupying forces, led by Major Paul Okuntimo of Rivers State Internal Security, claimed to be 'searching for those directly responsible for the killings of the four Ogonis.' However, witnesses say that they engaged in terror operations against the general Ogoni population. Amnesty International characterized the policy as deliberate terrorism. By mid-June, the security forces had razed 30 villages, detained 600 people and killed at least 40. This figure eventually rose to 2,000 civilian deaths and the displacement of around 100,000 internal refugees.[26][27]

In May 1994, nine activists from the movement who later became known as 'The Ogoni Nine', among them Ken Saro-Wiwa, were arrested and accused of incitement to murder following the deaths of four Ogoni elders. Saro-Wiwa and his comrades denied the charges, but were imprisoned for over a year before being found guilty and sentenced to death by a specially-convened tribunal, hand-selected by General Sani Abacha, on 10 November 1995. The activists were denied due process and upon being found guilty, were hanged by the Nigerian state.[28]

The executions met with an immediate international response. The trial was widely criticised by human rights organisations and the governments of other states, who condemned the Nigerian government's long history of detaining its critics, mainly pro-democracy and other political activists. The Commonwealth of Nations, which had pleaded for clemency, suspended Nigeria's membership in response to the executions. The United States, the United Kingdom, and the EU all implemented sanctions—but not on petroleum, Nigeria's primary export.

Shell claimed to have asked the Nigerian government to show clemency towards those found guilty,[29] but said its request was refused. However, a 2001 Greenpeace report found that "two witnesses that accused them [Saro-Wiwa and the other activists] later admitted that Shell and the military had bribed them with promises of money and jobs at Shell. Shell admitted having given money to the Nigerian military, who brutally tried to silence the voices which claimed justice".[30]

As of 2006, the situation in Ogoniland has eased significantly, assisted by the transition to democratic rule in 1999. However, no attempts have been made by the government or any international body to bring about justice by investigating and prosecuting those involved in the violence and property destruction that have occurred in Ogoniland,[31] although individual plaintiffs have brought a class action lawsuit against Shell in the US.[32]

Ijaw unrest (1998–1999)

[edit]The December 1998, All Ijaw Youths Conference crystallized the Ijaws' struggle for petroleum resource control with the formation of the Ijaw Youth Council (IYC) and the issuing of the Kaiama Declaration. In it, long-held Ijaw concerns about the loss of control over their homeland and their own lives to the oil companies were joined with a commitment to direct action. In the declaration, and in a letter to the companies, the Ijaws called for oil companies to suspend operations and withdraw from Ijaw territory. The IYC pledged "to struggle peacefully for freedom, self-determination and ecological justice," and prepared a campaign of celebration, prayer, and direct action, Operation Climate Change, beginning December 28.

In December 1998, two warships and 10–15,000 Nigerian troops occupied Bayelsa and Delta states as the Ijaw Youth Congress (IYC) mobilized for Operation Climate Change. Soldiers entered the Bayelsa, the state capital of Yenagoa, announced they had come because youths trying to stop the oil companies. On the morning of December 30, two thousand young people processed through Yenagoa, dressed in black, singing and dancing. Soldiers opened fire with rifles, machine guns, and tear gas, killing at least three protesters and arresting twenty-five more. After a march demanding the release of those detained was turned back by soldiers, three more protesters were shot dead including Nwashuku Okeri and Ghadafi Ezeifile. The military declared a state of emergency throughout Bayelsa State, imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew, and banned meetings. At military roadblocks, local residents were severely beaten or detained. At night, soldiers invaded private homes, terrorizing residents with beatings and raping the women and girls.

On January 4, 1999, about one hundred soldiers from the military base at Chevron's Escravos facility attacked Opia and Ikiyan, two Ijaw communities in Delta State. Bright Pablogba, the traditional leader of Ikiyan, who came to the river to negotiate with the soldiers, was shot along with a seven-year-old girl and possibly dozens of others. Of the approximately 1,000 people living in the two villages, four people were found dead and sixty-two were still missing months after the attack. The same soldiers set the villages ablaze, destroyed canoes and fishing equipment, killed livestock, and destroyed churches and religious shrines.

Nonetheless, Operation Climate Change continued, and disrupted Nigerian oil supplies through much of 1999 by turning off valves through Ijaw territory. In the context of high conflict between the Ijaw and the Nigerian Federal Government (and its police and army), the military carried out the Odi massacre, killing scores if not hundreds of Ijaws.

Subsequent actions by Ijaws against the oil industry included both renewed efforts at nonviolent action and attacks on oil installations and foreign oil workers.[33]

Creation of the Niger Delta Development Commission (2000–2003)

[edit]The Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) was established in 2000 by President Olusegun Obasanjo with the sole mandate of developing the petroleum-rich Niger-Delta region of southern Nigeria. Since its inauguration, the NDDC has focused on the development of social and physical infrastructures, ecological/environmental remediation and human development. The NDDC was created largely as a response to the demands of the population of the Niger Delta, a populous area inhabited by a diversity of minority ethnic groups. During the 1990s these ethnic groups, most notably the Ijaw and the Ogoni established organizations to confront the Nigerian government and multinational oil companies such as Shell. The minorities of the Niger Delta have continued to agitate and articulate demands for greater autonomy and control of the area's petroleum resources.[34]

Timeline

[edit]Emergence of armed groups in Niger Delta (2003–2004)

[edit]The ethnic unrest and conflicts of the late 1990s (such as those between the Ijaw, Urhobo and Itsekiri), coupled with a peak in the availability of small arms and other weapons, led increasingly to the militarization of the Delta. Local and state officials offered financial support to the paramilitary groups they believed would attempt to enforce their own political agenda. Conflagrations have been concentrated primarily in Delta and Rivers States.[35]

Prior to 2003, the epicenter of regional violence was Warri.[35] However, after the violent convergence of the largest military groups in the region, the Niger Delta People's Volunteer Force (NDPVF) led by Mujahid Dokubo-Asari and the Niger Delta Vigilantes (NDV) led by Ateke Tom (both of which are primarily made up of Ijaws), conflict became focused on Port Harcourt and outlying towns. The two groups dwarf a plethora of smaller militias, supposedly numbering more than one hundred. The Nigerian government classifies these groups as "cults", but many began as local university fraternities. The groups have adopted names largely based on Western culture, some of which include Icelanders, Greenlanders, KKK, and Vikings. All of the groups are constituted mostly by disaffected young men from Warri, Port Harcourt, and their suburban areas. Although the smaller groups are autonomous, they have formed alliances with and are largely controlled from above by either Asari and his NDPDF or Tom's NDV, who provide military support and instruction.

The NDPVF was founded by Asari, a former president of the Ijaw Youth Council, in 2003 after he "retreated into the bush" to form the group with the explicit goal of acquiring control of regional petroleum resources. The NDPFV attempted to control such resources primarily through oil "bunkering", a process in which an oil pipeline is tapped and the oil extracted onto a barge. Oil corporations and the Nigerian state point out that bunkering is illegal; militants justify bunkering, saying they are being exploited and have not received adequate profits from the profitable but ecologically destructive oil industry. Bunkered oil can be sold for profit, usually to destinations in West Africa, but also abroad. Bunkering is a fairly common practice in the Delta but in this case the militia groups are the primary perpetrators.[36]

The intense confrontation between the NDPVF and NDV seems to have been brought about by Asari's political falling out with the NDPVF's financial supporter Peter Odili, governor of Rivers State following the April 2003 local and state elections. After Asari publicly criticized the election process as fraudulent, the Odili government withdrew its financial support from the NDPVF and began to support Tom's NDV, effectively launching a paramilitary campaign against the NDPVF.

Subsequent violence occurred chiefly in riverine villages southeast and southwest of Port Harcourt, with the two groups fighting for control of bunkering routes. The conflagrations spurred violent acts against the local population, resulting in numerous deaths and widespread displacement. Daily civilian life was disrupted, forcing schools and economic activity to shut down, widespread property destruction resulted.

The state campaign against the NDPVF emboldened Asari who began publicly articulating populist, anti-government views and attempted to frame the conflict in terms of pan-Ijaw nationalism and "self-determination." Consequently, the state government escalated the campaign against him by bringing in police, army, and navy forces that began occupying Port Harcourt in June 2004.

The government forces collaborated with the NDV during the summer, and were seen protecting NDV militiamen from attacks by the NDPVF. The state forces failed to protect the civilian population from the violence and actually increased the destruction of citizens' livelihood. The Nigerian state forces were widely reported to have used the conflict as an excuse to raid homes, claiming that innocent civilians were cahoots with the NDPVF. Government soldiers and police obtained and destroyed civilian property by force. The NDPVF also accused the military of conducting air bombing campaigns against several villages, effectively reducing them to rubble, because they were believed to be housing NDPVF soldiers. The military denies this, claiming they engaged in aerial warfare only once in a genuine effort to wipe out an NDPVF stronghold.

Innocent civilians were also killed by NDPVF forces firing indiscriminately in order to engage their opponents. At the end of August 2004 there were several particularly brutal battles over the Port Harcourt waterfront; some residential slums were completely destroyed after the NDPVF deliberately burned down buildings. By September 2004, the situation was rapidly approaching a violent climax which caught the attention of the international community.[36]

Nigerian oil crisis (2004–2006)

[edit]After launching a mission to wipe out NDPVF, approved by President Olusegun Obasanjo in early September 2004, Mujahid Dokubo-Asari declared "all-out war" with the Nigerian state as well as the oil corporations and threatened to disrupt oil production activities through attacks on wells and pipelines.[37] This quickly caused a major crisis the following day on September 26, 2004, as Shell evacuated 235 non-essential personnel from two oil fields, cutting oil production by 30,000 barrels per day (4,800 m3/d).

Nigeria was the world's tenth largest oil exporter. The abundant oil reserves resulted in widespread exploitation. The Niger Delta region encompasses about 8% of Nigeria's landmass and is the largest wetlands region on the African continent. Oil drilling in the region began in the 1950s. In the beginning, the oil drilling in the region really stimulated Nigeria's economy and was extremely beneficial to the country. Numerous multinational corporations established oil operations in the region and made a conscious effort to not violate any environmental or human rights regulations. Shell began drilling in the Niger Delta region in 1956. Over time, Shell's presence in Nigeria has been very detrimental.[38]

These negative consequences are the result of thousands of oil spills, human rights violations, environmental destruction, and corruption. Over the past half century, Nigeria has become a plutocracy; political power is concentrated solely in the hands of the socioeconomic elite.[39] Shell's strong presence has played a major role in the absence of democracy in Nigeria. According to the documentary Poison Fire,[40] one and a half million tons of oil have been discharged into the Delta's farms, forests, and rivers since oil drilling began in 1956. This is equivalent to 50 Exxon Valdez disasters. Hundreds of kilometers of rain forest have been destroyed by the oil spills. When petroleum is discharged into the soil, the soil becomes acidic, which disrupts photosynthesis and kills trees because their roots are not able to get oxygen. Moreover, the fish population has also been negatively affected by oil drilling. The region is home to over 250 different fish species, and 20 of these species are found nowhere else in the world.[41] If oil spills continue at this rate entire species will become extinct and the entire Nigerian fishing industry will be decimated.

The oil spills in the Niger Delta also have negative implications on local human health. A primary cause of this is the effect crude oil spills have on crops in the given area. According to a Stanford University article, Oil Pollution in the Niger Delta,[42] there has been an estimation of 240,000 barrels of oil being spilled annually onto the Niger Delta region. Therefore, the prolificacy of this soil is prone to producing crops that contain higher amounts of metal than they would otherwise. Crops that prevailed in the oil spill, such as the pumpkin and the cassava, increased in lead absorption by over 90%.[43] Human Health Effects of Heavy Metals[44] addresses the harm lead and other metals can cause after strenuous exposure. Lead is a heavy metal that accumulates around regions that produce extreme amounts of fossil fuels and seep into products of consumption. Consuming lead is toxic enough to affect every organ and nervous system in the human body. Other detriments include the development of anemia, pregnancy miscarriages, wearing of body joints, and reduction of sperm efficiency. Another detrimental result of crude oil spills in the region is an increase of exposure to radiation, making individuals more prone to developing cancer.[43] Due to the circumstances, the Niger Delta is only capable of producing small portions of food unaffected by oil spills. This has increased hunger in families and individuals of all ages, leading to a country of predominant malnutrition. There is also a higher demand for food of good quality, but not enough monetary income, which leads to sex exchanges that ultimately transmit diseases such as HIV/AIDS, and increase teenage pregnancy and illegal abortions.[43] Citizens briefly mention their bodily experience when consuming local crops and protein in the HBO documentary, The Battle Raging in Nigeria over Control of Oil.

The implications on local human health are a direct consequence of environmental changes. As a result, there has been an influx of legal Acts and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) established between the early 80's and the early 2000s to reduce the crude oil damage in the Niger region. Part IV of Nigeria's Oil Pipelines Act (1990) addresses the laws of compensation for any damage done to the Nigerian community; oil companies are legally obligated by the judicial court to repay the country for harming their infrastructure and environment, so long as these affected regions are occupied by local people.[45] In the year 2000, the Niger Delta Development Commission(NDDC) was entrenched on the region with the purpose of encouraging environmental relief, preventing pollution, as well as locating and removing any inhibitions to community advancement. Developed in 1981 was one of the first NGO's to dedicate work towards oil spills, the Clean Nigeria Associates(N.C.A.). The N.C.A. currently consists of fifteen oil companies who attempt to tackle any pollutants that are being spilled into the Niger Delta's bodies of water. Multilateralism also plays a key role in the act of restoring the region. The United States provides the Nigerian Navy with equipped patrol boats to prevent oil smugglers from entering, leaving, or engaging in any business in the area.[46] Though action has been taken in the previous years, the Niger Delta continues to experience environmental and physical detriments with little to no legitimate interference from the oil companies involved.

Royal Dutch Shell controversy

[edit]Platform London, Friends of the Earth Netherlands (Milieudefensie) and Amnesty International have launched international campaigns aimed at having Shell clean the oil spills in the Delta. The organisations are concerned about the economic and health consequences for the people in the region. Shell's inability to respond effectively has led Friends of the Earth Netherlands and Amnesty International to believe it actively contributes to the human rights violations in the region. Because of the large area affected, the environmental consequences are vast.[47]

Piracy and kidnappings (2006–2014)

[edit]Starting in October 2012, Nigeria experienced a large spike in piracy off its coast. By early 2013 Nigeria became the second most-pirated nation in Africa, after Somalia. The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta is thought to be behind most of the attacks.[48] Since October 2012, MEND has hijacked 12 ships, kidnapped 33 sailors, and killed 4 oil workers. Since this started the United States has sent soldiers to train Nigerian soldiers in maritime tactics against pirates. Since this initiative began, 33 pirates have been captured. Although the Nigerian Navy now has learned new tactics to use against pirates, attacks still occur on a regular basis.

Since 2006, militant groups in Nigeria's Niger Delta, especially the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), have resorted to taking foreign employees of oil companies hostage. More than 200 foreigners have been kidnapped since 2006, though most were released unharmed.[49]

Military crackdown (2008–2009)

[edit]In August 2008, the Nigerian government launched a massive military crackdown on militants. They patrolled waters and hunted for militants, searched all civilian boats for weapons, and raided numerous militant hideouts.[50]

On May 15, 2009, a military operation undertaken by a Joint Task Force (JTF) began against MEND militants operating in the Niger Delta region.[51] It came in response to the kidnapping of Nigerian soldiers and foreign sailors in the Delta region.[52] Thousands of Nigerians have fled their villages and hundreds of people may be dead because of the offensive.[53]

Presidential amnesty program (2009–2016)

[edit]Pipeline attacks had become common during the insurgency in the Niger Delta, but ended after the government on June 26, 2009, announced that it would grant amnesty and an unconditional pardon to militants in the Niger Delta which would last for 60 days beginning on August 6, 2009, ending October 4, 2009. Former Nigerian President Umaru Musa Yar'Adua signed the amnesty after consultation with the National Council of State. During the 60-day period, armed youths were required to surrender their weapons to the government in return for training and rehabilitation by the government.[54] The program has been continued into the present.[55][56] Militants led their groups to surrender weapons such as rocket-propelled grenades, guns, explosives, and ammunition. Even gunboats have been surrendered to the government. Over 30,000 purported members signed up between October 2009 and May 2011 in exchange for monthly payments and in some cases lucrative contracts for guarding the pipelines. Though the programme has been extended through this year, the new government of Muhammadu Buhari sees it as a potentially enabling corruption and so feels that cannot be continued indefinitely.[57] The amnesty office has worked to reintegrate the fighters into society, primarily by placing and sponsoring them in vocational and higher education courses in Nigeria and abroad.[58]

The Presidential Amnesty Program (PAP) program proved to be a success, with violence and kidnappings decreasing sharply. Petroleum production and exports have increased from about 700,000 barrels per day (bpd) in mid-2009 to between 2.2 and 2.4 million bpd since 2011.[58] However, the program is costly and chronic poverty and catastrophic oil pollution that which fueled the earlier rebellion, remain largely unaddressed. With Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan's defeat in the March 2015 elections, the amnesty program seemed likely to end in December 2015 and with patronage to former militant leaders terminated, local discontent is deepening.[58]

2016 escalation

[edit]A February 2016 explosion in a pipeline operated by Shell Petroleum Development Corporation, a Royal Dutch Shell subsidiary to the Shell Forcados export terminal halted both production and imports. Speculation centered on militants using divers. Emmanuel Ibe Kachikwu, the minister of state for petroleum and the head of Nigeria's oil company[who?], said Nigerian production was down 300,000 barrels a day as a result.[57] On May 11, 2016, Shell closed its Bonny oil facility. Three soldiers guarding the installation were killed in an attack, said Col. Isa Ado of the Joint Military Force.[59] A bomb had closed down Chevron's Escravos GTL facility a week earlier.[59] On May 19, 2016, ExxonMobil's Qua Iboe shut down and evacuated its workers due to militant threats.[60]

The Niger Delta Avengers (NDA), a militant group in the Niger Delta, publicly announced its existence in March 2016.[61] The NDA have attacked oil-producing facilities in the delta, causing the shutdown of oil terminals and a fall in Nigeria's oil production to its lowest level in twenty years.[61] The attacks caused Nigeria to fall behind Angola as Africa's largest oil producer.[62] The reduced oil output has hampered the Nigerian economy and destroyed its budget,[63] since Nigeria depends on the oil industry for nearly all[clarification needed] its government revenue.[64]

In late August 2016, NDA declared a ceasefire and agreed to negotiate with the Nigerian government.[65][66] After declaration of ceasefire by Niger Delta Avengers, Reformed Egbesu Fraternities comprising the three militants groups Egbesu Boys of the Niger Delta, Egbesu Red Water Lions and Egbesu Mightier Fraternity; announced a 60-day ceasefire.[67]

On August 9, 2016, Niger Delta Greenland Justice Mandate declared its existence and threatened to destroy refineries in Port Harcourt and Warri within 48 hours, as well as a gas plant in Otu Jeremi within a few days.[68] The next day, the group reportedly blew up a major oil pipeline operated by the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) in Isoko.[69]

On August 12, 2016, the group warned that it will blow up additional oil installations in the future.[70]

On August 19, 2016, the group reportedly blew up two pipelines belonging to NPDC in the Delta State.[71]

On August 30, 2016, the group blew up the Ogor-Oteri oil pipeline.[72] On 4 September, the group claimed it had rigged all marked oil and gas facilities with explosives and warned residents living near them to evacuate[73]

Biafran insurgency

[edit]From early 2021, Niger Delta militant groups such as the "Niger Delta People's Salvation Force" led by Asari-Dokubo joined an insurgency in Southeastern Nigeria which pitted Biafran separatists against Nigerian security forces, armed Fulani herders, and bandits. Asari-Dokubo formed the "Biafra Customary Government" (BCG) in March 2021.[74][75] Igbos in the Niger Delta also joined the Biafran insurgency. Meanwhile, the Niger Delta Avengers continued to target and destroy pipelines, while local bandit groups exploited the unrest to stage raids.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Amnesty Programme: Niger Delta Revolutionary Crusaders berate those seeking to oust Prof. Dokubo". Vanguard-nigeria. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ^ Siarhei Bohdan.Belarusian Military Cooperation With Developing Nations: Dangerous Yet Legal // Belarus Digest, 5 December 2013

- ^ Нигерийские солдаты проходят специальную подготовку в Беларуси для борьбы с боевиками в дельте Нигера Archived 2018-07-16 at the Wayback Machine - Центр специальной подготовки Республики Беларусь {{in lang|ru}

- ^ "VK.com | VK". m.vk.com.

- ^ "Инструкторы из Израиля готовят нигерийский спецназ". Archived from the original on 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ^ Israel sends experts to help hunt for Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by Islamists. Archived 2018-09-10 at the Wayback Machine The Jerusalem Post; 05/20/2014 18:03.

- ^ Minahan, James B. (2016). "Urhobo". Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. p. 442–443. ISBN 978-1-61069-954-9.

- ^ a b c d e Tife Owolabi (14 June 2017). "New militant group threatens Niger Delta oil war - in Latin". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ ‘Asari Dokubo asking Niger Delta to join Biafra is a suicide mission’, PM News, 17 March 2021. Accessed 18 March 2021.

- ^ Ludovica Iaccino. "Pro-Biafrans claim Niger Delta Avengers link: Who is behind group that halted Nigeria's oil production?". IBTimes. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ a b Katrin Gänsler (3 September 2021). "In Biafra wächst die Unruhe". taz. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Nigeria's Cults and their Role in the Niger Delta Insurgency" by Bestman Wellington, The Jamestown Foundation, 6 July 2007

- ^ "BBC News - Nigerian militants seize workers from oil rig". bbc.co.uk. 2010-11-09. Archived from the original on 2011-01-26. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "FPIF". fpif.org. 2003-07-01. Archived from the original on 2011-01-26. Retrieved 2003-07-01.

- ^ "Background" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ ""Armed Conflicts Report - Nigeria"". Archived from the original on 2006-10-10. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Ehighelua, Ikhide (2007). Environmental Protection Law. New Pages Law Publishing Co. Effurun/Warri. pp. 247–250. ISBN 978-9780629328.

- ^ Koos, Carlo; Pierskalla, Jan (2015-01-20). "The Effects of Oil Production and Ethnic Representation on Violent Conflict in Nigeria: A Mixed-Methods Approach". Terrorism and Political Violence. 28 (5): 888–911. doi:10.1080/09546553.2014.962021. ISSN 0954-6553. S2CID 62815154.

- ^ "Violence in Nigeria's Oil Rich Rivers State in 2004 : Summary". Hrw.org. Archived from the original on 2008-11-02. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ a b Where Vultures Feast (Okonta and Douglas, 2001)

- ^ "Untitled". Essentialaction.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Mateos, Oscar (2021-06-21). "Understanding Niger Delta's violence from a World-Ecology perspective". Revista de Estudios en Seguridad Internacional. 7 (1): 29–43. doi:10.18847/1.13.4. ISSN 2444-6157. S2CID 237787893.

- ^ Obi, C. I.; Development, UN Research Institute for Social (2005). "Environmental movements in sub-Saharan Africa".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The Price of Oil: Corporate Responsibility and Human Rights Violations in Nigeria's Oil Producing Communities Archived May 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (Human Rights Watch, 1999)

- ^ "International Action Report" (PDF). Nigerianmuse.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Haller, Tobias; et al. (2000). Fossile Ressourcen, Erdölkonzerne und indigene Völker. Giessen: Focus Verlag. p. 105.

- ^ "Bogumil Terminski, Oil-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: Social Problem and Human Rights Issue" (PDF). Conflictrecovery.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Mathiason, Nick (2009-04-05). "Shell in court over alleged role in Nigeria executions | Business | The Observer". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ Nick Mathiason (April 4, 2009). "Shell in court over alleged role in Nigeria executions". Guardian. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ "Contamination in Paulina by Aldrin, Dieldrin, Endrin and other toxic chemicals produced and disposed of by Shell Chemicals of Brazil" (PDF). Greenpeace. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "THE NIGER DELTA: NO DEMOCRATIC DIVIDEND" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Shell hit by new litigation over Ogoniland". Mallenbaker.net. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Aghadiuno, Eric (1999-01-04). "Ijaw Tribe". OnlineNigeria.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-05. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ Ehighelua, Ikhide (2007). Environmental Protection Law. Effurun/Warri: New Pages Law Publishing Co. pp. 247–256. ISBN 978-9780629328.

- ^ a b Okonata, Ike; Douglas, Oronto (2003). Where Vultures Feast. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-473-1.

- ^ a b Rivers and Blood: Guns, Oil and Power in Nigeria's Rivers State Archived July 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (Human Rights Watch, 2005)

- ^ "Nigerian army warns oil rebels". 28 September 2014. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Antoni Pigrau (November 2013). "The environmental and social impact of Shell's operations in Nigeria". Per la Pau / Peace in Progress. International Catalan Institute for Peace. ISSN 2013-5777. Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ^ Ojukwu, Dr chris c; Nwaorgu, O. G. F. (2012-03-15). "Ideological Battle in the Nigerian State: An interplay of democracy and plutocracy". Global Journal of Human-Social Science. 12 (A6): 29–38. ISSN 2249-460X.

- ^ Maweni Farm Documentaries (15 July 2008). "Poison Fire". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2016-01-06. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ "World Wildlife Fund. 2006. Fishing on the Niger River. Retrieved May 10, 2007". Retrieved 13 June 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nwagbo, Gigi. "Oil Pollution in the Niger Delta". large.stanford.edu. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c Med, Niger (2013). "The human health implications of crude oil spills in the Niger delta, Nigeria: An interpretation of published studies". Nigerian Medical Journal. 54 (1): 10–16. doi:10.4103/0300-1652.108887. PMC 3644738. PMID 23661893.

- ^ Martin, Sabine; Griswold, Wendy. "Human Health Effects of Heavy Metals". Center for Hazardous Substance Research. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.399.9831.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Oil Pipelines Act [Chapter 338] (IV). Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 1990. 1990.

- ^ Nwilo, PC; Badejo, OT (2005). "Oil Spill Problems and Management in the Niger Delta". International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings. 2005. Department of Surveying & Geoinformatics: 567–570. doi:10.7901/2169-3358-2005-1-567.

- ^ "Worse Than Bad". Milieudefensie.nl. Archived from the original on 2012-06-11. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- ^ "Nigeria's shadowy oil rebels". 20 April 2006. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016 – via bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Philp, Catherine (January 19, 2009). "British hostages moved by Niger rebels after botched rescue". The Times. London. Retrieved May 2, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Military operations in the Niger Delta - 16 Aug 08 on YouTube[dead link]

- ^ Fatade, Wale (2009-05-28). "Niger Delta offensive intensifies". 234next.com. Archived from the original on 2016-02-18. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ Walker, Andrew (2009-05-27). "Africa | Will Nigeria oil offensive backfire?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2009-09-30. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "IRIN Africa | NIGERIA: Thousands flee violence, hundreds suspected dead | Nigeria | Conflict | Economy | Environment". Irinnews.org. 2009-05-22. Archived from the original on 2011-01-27. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "Africa | Nigeria offers militants amnesty". BBC News. 2009-06-26. Archived from the original on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "Engaging the Nigerian Niger Delta Ex-Agitators: The Impacts of the Presidential Amnesty Program to Economic Development" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ "Why Buhari Will Sustain Amnesty Programme – Presidency - INFORMATION NIGERIA". 25 April 2015. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ a b Maggie Fick in Lagos; Anjli Raval in London (March 8, 2016). "Bombed pipeline to hit Nigeria oil output". Financial Times.

- ^ a b c "Curbing Violence in Nigeria (III): Revisiting the Niger Delta". Crisis Group. 29 September 2015. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016.

- ^ a b Hilary Uguru; Michelle Faul (May 11, 2016). "Shell Nigeria shuts oil terminal as attacks cut production". Seattle Times. AP. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ Jarrett Renshaw; Libby George; Simon Falush (May 19, 2016). "Nigeria's Qua Iboe crude oil terminal closed, workers evacuated - traders". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "Nigeria arrests 'Avengers' oil militants". BBC News Online. 16 May 2016. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Elena Holodny (16 May 2016). "Africa's largest oil producer has been dethroned". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "The Niger Delta Avengers: Danegeld in the Delta". The Economist. 25 June 2016. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "Avengers unite! Violence in the Delta has cut oil output by a third. It may get even worse". The Economist. 25 June 2016. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "Rebels in Niger Delta cease attacks on oil platforms, agree to peace talks". Deutsche Welle. 21 August 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Rebels in Niger Delta cease attacks on oil platforms, agree to peace talks". Pulse.ng. 21 August 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "N'Delta Militants: More Groups Declare Ceasefire". Reports Afrique News. 22 August 2016. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Niger Delta: Another militant group emerges, vows to bring down refineries in Port Harcourt, Warri within 48 hours". Daily Post. 9 August 2016. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "New Niger Delta militant group, Greenland blows up oil pipeline in Delta". Daily Post. 10 August 2016. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Niger Delta militants issue another deadly warning". News24. 12 August 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Suspected Niger Delta militants blow up two NPDC pipelines in Delta". Daily Post. 19 August 2016. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "JUST IN: Militants strike again, blow up NPDC facility". Naij. 30 August 2016. Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Militants tell residents to vacate oil facilities". Naij. 4 September 2016. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Biafra Struggle: How Nnamdi Kanu, Asari Dokubo Fell Out". Sahara Reporters. 15 June 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ ‘Nobody can stop us’ — Asari Dokubo declares Biafra government, The Cable, 14 March 2021. Accessed 15 March 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Obi, Cyril and Siri Aas Rustad (2011). Oil and insurgency in the Niger Delta : managing the complex politics of petro-violence. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84813-808-7.

- Maier, Karl (2002). This House Has Fallen: Nigeria in Crisis (illustrated, reprint ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 9780813340456.

- Lorne Stockman; James Marriott; Andrew Rowell (3 Nov 2005). The Next Gulf: London, Washington and Oil Conflict in Nigeria. Constable & Robinson Ltd. ISBN 978-1845292591.

- Peel, Michael (24 Mar 2011). A Swamp Full of Dollars: Pipelines and Paramilitaries at Nigeria's Oil Frontier (illustrated, reprint ed.). I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1848858404.

External links

[edit]- SPECIAL REPORT: Checkmating the Resurgence of Oil Violence in the Niger Delta of Nigeria Journal of Energy Security, May 2010

- Peace and Security in the Niger Delta: Baseline Study WAC Global Services Baseline Study, December 2003

- Other Separatist Groups - MASSOB-Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra

- "Blood Oil" by Sebastian Junger in Vanity Fair, February 2007 (accessed 28 January 2007)

- Nigerian Oil -- "Curse of the Black Gold: Hope and Betrayal in the Niger Delta"—article from National Geographic Magazine (February 2007)

- A Look At the Fight Over Nigeria's Natural Resources December 26, 2006

- Environmental Pollution in Niger Delta Region of Nigeria: The Conceptual Inadequacy of ‘Environmental Justice’