Lolita (1962 film)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

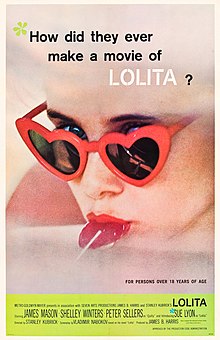

| Lolita | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by | Vladimir Nabokov[1][2] |

| Based on | Lolita 1955 novel by Vladimir Nabokov |

| Produced by | James B. Harris |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Anthony Harvey |

| Music by | Nelson Riddle |

| Theme song by | Bob Harris |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 152 minutes[7] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5–2 million[5][8] |

| Box office | $9.2 million[8] |

Lolita is a 1962 black comedy-psychological drama film[9] directed by Stanley Kubrick, based on the 1955 novel of the same name by Vladimir Nabokov.

The black-and-white film follows a middle-aged literature lecturer who writes as "Humbert" and has hebephilia. He is sexually infatuated with young, adolescent Dolores Haze (whom he calls "Lolita"). It stars James Mason as Humbert, Shelley Winters as Mrs. Haze, Peter Sellers as Quilty, and Sue Lyon (in her film debut) as Dolores "Lolita" Haze.

The novel was considered "unfilmable" when Kubrick acquired the rights around the time of its U.S. publication. Owing to restrictions imposed by the Motion Picture Production Code (1934–68), the film toned down the most provocative aspects, sometimes leaving much to the audience's imagination. Sue Lyon was 14 at the time of filming and played a 17-year-old, whereas the Lolita of Nabokov's novel is just 12 years old when Humbert Humbert first meets her.

Lolita polarized contemporary critics with its theme of child sexual abuse but was nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 35th Academy Awards. Years after its release, Kubrick expressed doubt that he would have attempted to make the film had he fully understood how severe the censorship limitations on it would be. Regardless, the film has since received critical acclaim. In the late 1990s, British director Adrian Lyne again adapted the novel to the big screen.

Plot

[edit]Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged European professor of French literature, arrives in Ramsdale, New Hampshire, intending to spend the summer before his professorship begins at Beardsley College, Ohio. He searches for a room to rent, and Charlotte Haze, a sexually frustrated widow, invites him to stay at her house. After declining, he sees her 17-year-old daughter, Dolores, affectionately nicknamed "Lolita".

Infatuated with Dolores, Humbert accepts Charlotte's offer and becomes a lodger in the Haze household. However, Charlotte wants all of Humbert's time for herself and plans to send Dolores to an all-girl sleepaway camp for the summer. After the Hazes depart for camp, the maid gives Humbert a letter from Charlotte, confessing her love for him and demanding that he vacate at once unless he feels the same way. The letter says that if Humbert is still in the house when she returns, Charlotte will know her love is requited, and he must marry her. Despite laughing while reading the letter, Humbert marries Charlotte.

In Lolita's absence, glum Humbert becomes more withdrawn, and Charlotte grows increasingly unfulfilled and upset. Charlotte discovers Humbert's diary entries detailing his passion for Dolores and describing Charlotte as "obnoxious" and "brainless". Distraught, she runs outside, but is hit by a car and dies.

Humbert arrives to pick up Dolores from camp; she does not yet know that Charlotte died. They stay the night in a hotel that is handling an overflow influx of police officers attending a convention. One of the guests insinuates himself upon Humbert and keeps steering the conversation to his "beautiful little daughter", who is asleep upstairs. The stranger implies that he too is a policeman and repeats that he thinks Humbert is "normal". Humbert escapes the man's advances. The next morning, Humbert and Dolores play a "game" she learned at camp, and it is implied that they have a sexual encounter. The next day, Humbert confesses to Dolores that Charlotte is not sick in a hospital, as he had previously said, but dead. Grief-stricken, she stays with Humbert. The two commence a trip cross country, traveling from hotel to motel. In public, they act as father and daughter.

In the fall, Humbert reports to his position at Beardsley College, and enrolls Dolores in high school there. People begin to wonder about the relationship between the two. Humbert worries about her involvement with the school play and with male classmates. One night, he returns home to find a stranger who calls himself Dr. Zempf, sitting in his darkened living room. Zempf claims to be the psychologist from Dolores's school and wants to discuss her knowledge of "the facts of life". He convinces Humbert to allow Dolores to participate in the school play, for which she had been selected to play the leading role.

While attending a performance of the play, Humbert learns that Dolores has been lying about how she was spending her Saturday afternoons when she claimed to be at piano practice. They get into a row and Humbert decides to leave Beardsley College and take Dolores on the road again. Dolores objects at first but then changes her mind and seems enthusiastic. Once on the road, Humbert realizes that they are being followed by a car which never drops away. When Dolores becomes sick, he takes her to the hospital. However, when he returns to pick her up, she is gone. The nurse says that Dolores left with a man who claimed to be her uncle. Humbert is devastated.

Years later, he receives a letter from Mrs. Richard T. Schiller, Dolores's married name. Dolores writes that she is now married to a man named Dick and that she is pregnant and in desperate need of money. Humbert visits her and demands that she tell him who kidnapped her three years earlier. She says that it was Clare Quilty, the man who was following them. A famous playwright, he had a fling with Charlotte in Ramsdale. She states that Quilty is also the one who disguised himself as Dr. Zempf, the stranger who kept crossing their path. Dolores was infatuated by Quilty and carried on an affair with him at Beardsley, then left the hospital with him when he promised her a Hollywood contract. However, he then demanded that she join his bohemian lifestyle, including acting in his "art" films, which she refused.

Humbert begs Dolores to leave Schiller and come away with him. She refuses, as she has a baby due in three months, but apologizes for cheating. Humbert gives Dolores $13,000, explaining that it is her money from the sale of Charlotte's house. He then leaves to confront Quilty in his mansion. There, a drunk Quilty is shot dead by Humbert. Humbert later dies of coronary thrombosis awaiting trial for Quilty's murder.

Cast

[edit]- James Mason as Humbert "Hum" Humbert

- Shelley Winters as Charlotte Haze-Humbert

- Sue Lyon as Dolores "Lolita" Haze

- Peter Sellers as Clare Quilty / Dr. Zempf

- Gary Cockrell as Richard "Dick" Schiller

- Jerry Stovin as John Farlow, Ramsdale Lawyer

- Diana Decker as Jean Farlow

- Lois Maxwell as Nurse Mary Lore

- Cec Linder as Dr. Keegee

- Susanne Gibbs as Mona

- Bill Greene as George Swine, The Hotel Night Manager In Bryceton

- Shirley Douglas as Mrs. Starch, The Piano Teacher In Ramsdale

- Marianne Stone as Vivian Darkbloom, Quilty's Companion

- Marion Mathie as Miss Lebone

- James Dyrenforth as Frederick Beale Sr.

- Maxine Holden as Miss Fromkiss, The Hospital Receptionist

- John Harrison as Tom

- Colin Maitland as Charlie Sedgewick

- C. Denier Warren as Potts

- Ed Bishop as Ambulance Attendant

Production

[edit]

Stanley Kubrick and James Harris acquired the right to Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita, a novel considered unfilmable, several years after it was first published in September 1955 in Paris by Maurice Girodias' Olympia Press, which specialized in pornographic literature. Initially considered a "dirty book" in an era when literary censorship meant jail time and fines for publishers, Lolita was not published in the United States until August 1958 by G.P. Putnam's Sons, after it had gradually established its literary reputation.

Nabokov had submitted the novel to Girodias after it was rejected by mainstream publishers. The book received no reviews until Graham Greene ranked it at one of the three best books of 1955 in the London Sunday Times. London Sunday Express editor John Gordon, in response to Greene, called it "the filthiest book I have ever read" and "sheer unrestrained pornography". The book was deemed pornography by the Home Office and British Customs officers were instructed to seize all copies entering the United Kingdom. France banned the novel for two years (1956–58). Lolita was not published in the UK until 1959.[10]

When Marlon Brando fired Kubrick from One-Eyed Jacks project in November 1958, the director issued a press release saying that he was resigning from Brando's picture "with deep regret" so that he could "commence work on Lolita".[11] Kubrick was hired by Kirk Douglas to replace director Anthony Mann on the epic Spartacus; he and Harris didn't put Lolita into production until 1960. Kubrick directed Laurence Olivier and Peter Ustinov in Spartacus, both of whom he considered for roles in his Lolita adaptation. It was filmed, in part, in Great Britain, and in Albany, New York.[5]

Direction

[edit]With Nabokov's consent, Kubrick changed the order in which events unfolded by moving what was the novel's ending to the start of the film. Kubrick determined that while this sacrificed a great ending, it helped maintain interest, as he believed that interest in the novel sagged after Humbert "seduced" Lolita halfway through.[12]

The second half contains an odyssey across the United States and though the novel was set in the 1940s, Kubrick gave it a contemporary setting, shooting many of the exterior scenes in England with some back-projected scenery shot in the United States, including upstate eastern New York, along NY 9N in the eastern Adirondacks, and a hilltop view of Albany from Rensselaer, on the east bank of the Hudson.[citation needed]

Some of the minor parts were played by Canadian and American actors, such as Cec Linder, Lois Maxwell, Jerry Stovin and Diana Decker, who were based in England at the time. Kubrick had to film in England, as much of the money to finance the film was raised there, with the condition that it also be spent there.[12] In addition, Kubrick had been living in England since 1961 and suffered from a deathly fear of flying.[13] Hilfield Castle is featured in the film as Quilty's "Pavor Manor".

Casting

[edit]James Mason was the first choice of Kubrick and producer Harris for the role of Humbert Humbert, but he initially declined due to a Broadway engagement while recommending his daughter, Portland, for the role of Lolita.[14] Laurence Olivier, who co-starred in Kubrick's Spartacus, was offered the part but turned it down, apparently on the advice of his agents who also represented Kubrick.[citation needed]

Kubrick then considered Peter Ustinov, who won an Oscar for Spartacus, but decided against him. Harris suggested David Niven, who accepted the part but withdrew for fear that the sponsors of his TV show, Four Star Playhouse (1952), would object to the subject matter. Noël Coward and Rex Harrison were also considered.[15]

Mason got the part of Humbert Humbert when he withdrew from the play.[citation needed]

The role of Clare Quilty was greatly expanded from that in the novel and Kubrick allowed Sellers to adopt a variety of disguises throughout the film. Early on in the film, Quilty appears as himself: a conceited, avant-garde playwright with a superior manner. Later he is an inquisitive policeman on the porch of the hotel, where Humbert and Lolita are staying. Next he is the intrusive Beardsley High School psychologist, Doctor Zempf. He persuades Humbert to give Lolita more freedom in her after-school activities.[16] He is seen as a photographer backstage at Lolita's play. Later in the film, he is an anonymous phone caller conducting a survey.

Jill Haworth was asked to take the role of Lolita but she was under contract to Otto Preminger and he said "no".[17] Hayley Mills was offered the role but her parents refused permission for her to do it.[18] Joey Heatherton, Sandra Dee, and Tuesday Weld also were potential candidates for the role.[citation needed]

Although Vladimir Nabokov originally thought that Sue Lyon was the right selection to play Lolita, years later, Nabokov said that the ideal Lolita would have been Catherine Demongeot, a young French actress who had played the child Zazie in Louis Malle's Zazie in the Metro (1960). Demongeot was four years younger than Lyon.[19]

Lyon's age

[edit]Producer James Harris explained that 14-year-old Sue Lyon, who looked older than her age, was cast because "we knew we must make [Lolita] a sex object [...] where everyone in the audience could understand why everyone would want to jump on her."[20] He also said, in a 2015 Film Comment interview, "We made sure when we cast her that she was a definite sex object, not something that could be interpreted as being perverted."[21]

Harris said that he and Kubrick, through casting, changed Nabokov's book as "we wanted it to come off as a love story and to feel very sympathetic with Humbert."[22]

Censorship

[edit]

At the time the film was released, the ratings system was not in effect and the Hays Code, dating back to the 1930s, governed film production. The censorship of the time inhibited Kubrick's direction; Kubrick later commented that, "because of all the pressure over the Production Code and the Catholic Legion of Decency at the time, I believe I didn't sufficiently dramatize the erotic aspect of Humbert's relationship with Lolita. If I could do the film over again, I would have stressed the erotic component of their relationship with the same weight Nabokov did."[12] Kubrick hinted at the nature of their relationship indirectly, through double entendre and visual cues such as Humbert painting Lolita's toes. In a 1972 Newsweek interview (after the ratings system had been introduced in late 1968), Kubrick said that he "probably wouldn't have made the film" had he realized in advance how difficult the censorship problems would be.[23]

The film is deliberately vague over Lolita's age. Kubrick commented, "I think that some people had the mental picture of a nine-year-old, but Lolita was twelve and a half in the book; Sue Lyon was thirteen." Actually, Lyon was 14 by the time filming started and 15 when it finished.[24] Although passed without cuts, Lolita was rated "X" by the British Board of Film Censors when released in 1962, meaning no one under 16 years of age was permitted to watch.[25]

Voice-over narration

[edit]Humbert uses the term "nymphet" to describe Lolita, which he explains and uses in the novel; it appears twice in the film and its meaning is left undefined.[26] In a voice-over on the morning after the Ramsdale High School dance, Humbert confides in his diary, "What drives me insane is the twofold nature of this nymphet, of every nymphet perhaps, this mixture in my Lolita of tender, dreamy childishness and a kind of eerie vulgarity. I know it is madness to keep this journal, but it gives me a strange thrill to do so. And only a loving wife could decipher my microscopic script."

Screenplay adaptation

[edit]The screenplay is credited to Nabokov, although very little of what he provided (later published in a shortened version[1][2]) was used in the film itself.[27] Nabokov, following the success of the novel, moved out to Hollywood and penned a script for a film adaptation between March and September 1960. The first draft was extremely long—over 400 pages. As producer Harris remarked, "You couldn't make it. You couldn't lift it".[28] Nabokov remained polite about the film in public but in a 1962 interview before seeing the film, commented that it may turn out to be "the swerves of a scenic drive as perceived by the horizontal passenger of an ambulance".[29]

Music

[edit]The music for the film was composed by Nelson Riddle and Bob Harris (the main theme was solely by Bob Harris), and performed by Riddle's orchestra. The recurring dance number first heard on the radio when Humbert meets Lolita in the garden later became a hit single under the name "Lolita Ya Ya" with Sue Lyon credited with the singing on the single version.[30] The flip side was a 60s-style light rock song called "Turn off the Moon" penned by Harris and Al Stillman and also sung by Sue Lyon. There is also a version released as a single credited to Nelson Riddle on the "B-side" of his Route 66 Theme (Capitol 4741). "Lolita Ya Ya" was later recorded by other bands; it was also a 1962 hit single for The Ventures, reaching 61 on the Billboard Hot 100.[31] A review in Billboard stated, "There've been a number of versions of the title tune from the hit film Lolita but this figures the strongest to date. The usual Ventures guitar sound is neatly augmented with voices."[32]

Reception

[edit]Lolita premiered on June 13, 1962, in New York City (the copyright date onscreen is 1961). It performed fairly well with little advertising, relying mostly on word-of-mouth; many critics seemed uninterested or dismissive of the film while others gave it glowing reviews. However, the film was very controversial, due to the hebephilia-related content.[33][34]

Among the positive reviews, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that the film was "conspicuously different" from the novel and had "some strange confusions of style and mood", but nevertheless had "a rare power, a garbled but often moving push toward an off-beat communication."[35] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called it "a peculiarly brilliant film", with a tone "not of hatred, but of mocking true. Director and author have a viewpoint on modern life that is not flattering but it is not despising, either. It is regret for the human comedy."[36] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times declared that the film "manages to hit peaks of comedy shrilly dissonant but on an adult level, that are rare indeed, and at the same time to underline the tragedy in human communication, human communion, between people who've got their signals hopelessly crossed."[37] The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that the primary themes of the film were "obsession and incongruity", and since Kubrick was "an intellectual director with little feeling for erotic tension ... one is the more readily disposed to accept Kubrick's alternative approach as legitimate."[38] In a generally positive review for The New Yorker, Brendan Gill wrote that "Kubrick is wonderfully self-confident; his camera having conveyed to us within the first five minutes that it can perform any wonders its master may require of it, he proceeds to offer us a succession of scenes broadly sketched and broadly acted for laughs, and laugh we do, no matter how morbid the circumstances."[39] Arlene Croce in Sight & Sound wrote that "Lolita is—in its way—a good film." She found Nabokov's screenplay "a model of adaptation" and the cast "near-perfect", though she described Kubrick's attempts at eroticism as "perfunctory and misguided" and thought his "gift for visual comedy is as faint as his depiction of sensuality."[40]

Variety had a mixed assessment, calling the film "occasionally amusing but shapeless", and likening it to "a bee from which the stinger has been removed. It still buzzes with a sort of promising irreverence, but it lacks the power to shock and eventually makes very little point either as comedy or satire."[41] Harrison's Reports was negative, writing, "You don't have to be an emulating, prissyish uncle from Dubuque to say that the film leaves you with a feeling that is repulsively disgusting in much of its telling," adding that "even if the exhibitor makes a dollar on the booking, he may feel a sense of shame as he plods his weary way down to the bank."[42] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic called Lolita "tantalizingly unsatisfactory".[43]

The film has been re-appraised by critics over time, and currently has a score of 91% on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes based on 44 reviews and with an average rating of 7.9/10. The critical consensus reads: "Kubrick's Lolita adapts its seemingly unadaptable source material with a sly comedic touch and a sterling performance by James Mason that transforms the controversial novel into something refreshingly new without sacrificing its essential edge."[44] Metacritic gives the film a score of 79 out of 100, based on reviews by 14 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[45] Filmmaker David Lynch has said that Lolita is his favorite Kubrick film.[46] Sofia Coppola has also cited Lolita as one of her favorite films,[47] as has Paul Thomas Anderson.[48]

The film was a commercial success. Produced on a budget of around $2 million, Lolita grossed $9,250,000 domestically.[5][8] During its initial run, the film earned an estimated $4.5 million in North American rentals.[49]

Years after the film's release it has been re-released on VHS, Laserdisc, DVD, and Blu-ray.

Awards and honors

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[50] | Best Screenplay – Based on Material from Another Medium | Vladimir Nabokov | Nominated |

| British Academy Film Awards[51] | Best British Actor | James Mason | Nominated |

| Directors Guild of America Awards[52] | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Stanley Kubrick | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards[53] | Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama | James Mason | Nominated |

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Shelley Winters | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Peter Sellers | Nominated | |

| Best Director – Motion Picture | Stanley Kubrick | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Newcomer – Female | Sue Lyon | Won | |

| Saturn Awards (2011) | Best DVD Collection | Lolita (As part of Stanley Kubrick: The Essential Collection) | Won |

| Saturn Awards (2014) | Best DVD or Blu-ray Collection | Lolita (As part of Stanley Kubrick: The Masterpiece Collection) | Nominated |

| Venice International Film Festival | Golden Lion | Stanley Kubrick | Nominated |

Controversy

[edit]A 2020 article by journalist Sarah Weinman alleges that Harris, the producer of the film, had sex with Lyon during the shooting of the film when she was 14 years old. Although Lyon had remained silent regarding the rumors for many years, when asked for a statement on the planned remake of the film in 1996, she had stated:[54]

My destruction as a person dates from that film. Lolita exposed me to temptations no girl of that age should undergo. I defy any pretty girl who is rocketed to stardom at 14 in a sex nymphet role to stay on a level path thereafter.

Alternate versions

[edit]- The scene where Lolita first "seduces" Humbert as he lies on the cot is approximately 10 seconds longer in the British and Australian cut of the film. In the U.S. edition, the shot fades as she whispers the details of the "game" she played with Charlie at camp. In the UK/Australian print, the shot continues as Humbert mumbles that he is not familiar with the game. She then bends down again to whisper more details. Kubrick then cuts to a closer shot of Lolita's face as she says "Well, alrighty then" and then fades as she begins to descend onto Humbert on the cot. The latter cut of the film was used for the Region 1 DVD release. It is also the version aired on Turner Classic films in the U.S.[citation needed]

- The Criterion LaserDisc release is the only one to use a transfer approved by Stanley Kubrick. This transfer alternates between a 1.33 and a 1.66 aspect ratio (as does the Kubrick-approved Strangelove transfer). All subsequent releases to date have been 1.66 (which means that all the 1.33 shots are slightly matted).[citation needed]

Other film adaptations

[edit]Lolita was filmed again in 1997, directed by Adrian Lyne, starring Jeremy Irons as Humbert, Melanie Griffith as Charlotte and Dominique Swain as Lolita. The film was widely publicized as being more faithful to Nabokov than the Kubrick film. Although many observed this was the case (such as Erica Jong writing in The New York Observer),[55] the film was not as well received as Kubrick's version, and was a major box office bomb, first shown on the Showtime cable network, then released theatrically, grossing only $1 million at the US box office based on a $62 million budget.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bailey, Blake (June 11, 2014). "Vladimir Nabokov's Unpublished 'Lolita' Screenplay Notes". Vice. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Nabokov, Vladimir (August 26, 1997). Lolita: A Screenplay. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-679-77255-2.

- ^ "SK – Stanley Kubrick Archive". archives.arts.ac.uk. University of the Arts London. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

Lolita (production Harris Kubrick Pictures, A.A. Productions, distributor Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc.) followed in 1962, a time when content of the film still had the potential to offend censorship boards. Kubrick was acutely aware of this and its potential to damage commercial success and so the film was carefully crafted to avoid this. Lolita was also the first of Kubrick's films to be made in England, it was mainly filmed at MGM studios in Borehamwood. Initially Kubrick's move to the UK was financial, MGM had money that they had to spend on a UK film production.

- ^ "DS/UK/384". archives.arts.ac.uk. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

Kubrick company, only did Lolita

- ^ a b c d "Lolita". Catalog – American Film Institute. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ "Lolita (1962)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ "Lolita (1962)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c Box Office Information for Lolita Archived February 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The Numbers. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ "Lolita". AllMovie.

- ^ Boyd, Brian (1991). Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06797-1.

- ^ Hughes, David (2013). The Complete Kubrick. London: Vrigin Pub. p. Paperback. ISBN 978-0-7535-1272-2. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c "An Interview with Stanley Kubrick (1969)" by Joseph Gelmis. Excerpted from The Film Director as Superstar (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1970).

- ^ Rose, Lloyd. "Stanley Kubrick, at a Distance" Washington Post (June 28, 1987)

- ^ "Portland Mason". Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ "Lolita (1962)".

- ^ "Kubrick in Nabokovland" by Thomas Allen Nelson. Excerpted from Kubrick: Inside a Film Artist's Maze (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000, pp 60–81)

- ^ Lisanti, Tom (2001), Fantasy Femmes of Sixties Cinema: Interviews with 20 Actresses from Biker, Beach, and Elvis Movies, McFarland, p. 71, ISBN 978-0-7864-0868-9

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (March 19, 2022). "Movie Star Cold Streaks: Hayley Mills". Filmink.

- ^ Boyd, Brian (1991). Vladimir Nabokov: the American years. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-691-02471-4. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ "The troubling legacy of the Lolita story, 60 years on". www.bbc.com. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Interview: James B. Harris (Part One)". Film Comment. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ Green, Steph. "The troubling legacy of the Lolita story, 60 years on". bbc.com. British Broadcasting Corp. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "'Lolita': Complex, often tricky and 'a hard sell'". CNN. Archived from the original on January 3, 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Graham Vickers (August 1, 2008). Chasing Lolita: How Popular Culture Corrupted Nabokov's Little Girl All Over Again. Chicago Review Press. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-1-55652-968-9.

- ^ "Lolita (15)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ "Lolita (1962)" A Review by Tim Dirks—A comprehensive review containing extensive dialogue quotes. These quotes include other details of Humbert's narration.

- ^ Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide 2013 Edition (edited by Leonard Maltin, a Signet Books paperback published by New American Library, a division of Penguin Group), p. 834: "Screenplay for this genuinely strange film is credited to Vladimir Nabokov, who wrote the novel of the same name, but bears little relation to his actual script, later published"

- ^ Naremore, James (2019). On Kubrick. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-83871-746-9.

- ^ Nabokov, Strong Opinions, Vintage International Edition, pp. 6–7

- ^ Tony Maygarden. "SOUNDTRACKS TO THE FILMS OF STANLEY KUBRICK". The Endless Groove. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ^ "Lolita Ya-Ya". Billboard Database. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ "Singles Reviews". Billboard. July 14, 1962. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ PAI RAIKAR, RAMNATH N (August 8, 2015). "Lolita: The girl who knew too much". Navhind Times. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ "Lolita (película de 1997)" (in Spanish). Helpes.eu. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (June 14, 1962). "Screen: 'Lolita,' Vladimir Nabokov's Adaptation of His Novel". The New York Times: 23.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (June 29, 1962). "'Lolita' Still Is Provocative". The Washington Post. p. C5.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (June 17, 1962) "'Lolita,' Naughty but Nicer, Arrives as Movie". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 8.

- ^ "Lolita". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 29 (345): 137. October 1962.

- ^ Gill, Brendan (June 23, 1962). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 90.

- ^ Croce, Arlene (Autumn 1962). "Film Reviews: Lolita". Sight & Sound. 31 (4): 191.

- ^ "Lolita". Variety: 6. June 13, 1962.

- ^ "Film Review: Lolita". Harrison's Reports: 94. June 23, 1962.

- ^ Kaufmann, Stanley (1968). A world on Film. Delta Books. p. 17.

- ^ Lolita at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ "Lolita (1962) Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ "David Lynch on Stanley Kubrick". YouTube. May 13, 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ Ferrier, Aimee (April 20, 2024). "Sofia Coppola names her favourite Stanley Kubrick movie". Far Out. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ Ferrier, Aimee (September 22, 2022). "Paul Thomas Anderson on his favourite Stanley Kubrick movies". Far Out. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ "All-Time Top Grossers". Variety. January 8, 1964. p. 69.

- ^ "The 35th Academy Awards (1963) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1963". BAFTA. 1963. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "15th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Lolita – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Weinman, Sarah (October 24, 2020). "The Dark Side of Lolita". Air Mail. No. 67. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Erica Jong Screens Lolita With Adrian Lyne". The New York Observer . May 31, 1998. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Corliss, Richard (1994). Lolita. British Film Institute. ISBN 0-85170-368-2.

- Hughes, David (2000). The Complete Kubrick. Virgin Publishing. ISBN 0-7535-0452-9.

- Fenwick, James (May 19, 2023). "The exploitation of Sue Lyon: Lolita (1962), archival research, and questions for film history". Feminist Media Studies. 23 (4): 1786–1801. doi:10.1080/14680777.2021.1996422. S2CID 240267605.

- Trubikhina, Julia (2007). "Struggle for the Narrative: Nabokov and Kubrick's Collaboration on the "Lolita" Screenplay". Ulbandus Review. 10: 149–172. ISSN 0163-450X. JSTOR 25748170.

- Keller, Cote (May 2, 2018). "Stanley Kubrick & The Evolution of Critical Consensus". Global Tides. 12 (1). Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- Southern, Terry (1962). "An Interview with Stanley Kubrick, Director of Lolita". Esquire. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008.

unpublished

- Southern, Terry; Southern, Nile (Fall 2004). "Check-Up With Dr. Strangelove". Filmmaker Magazine.

External links

[edit]- Lolita at IMDb

- Lolita at AllMovie

- Lolita at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Lolita at the TCM Movie Database

- Lolita at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1962 films

- 1962 comedy-drama films

- 1962 black comedy films

- 1962 romantic comedy films

- 1962 romantic drama films

- 1960s psychological drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American comedy-drama films

- American nonlinear narrative films

- American romantic drama films

- British black-and-white films

- British comedy-drama films

- British nonlinear narrative films

- Censored films

- Films about child sexual abuse

- Films about educators

- Films about orphans

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on works by Vladimir Nabokov

- Films directed by Stanley Kubrick

- Films scored by Nelson Riddle

- Films set in New Hampshire

- Films set in Ohio

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films shot at Associated British Studios

- Films about incest

- Films about juvenile sexuality

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Rating controversies in film

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s American films

- 1960s British films

- Films about pedophilia

- Lolita

- Saturn Award–winning films

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language romantic comedy films

- English-language romantic drama films

- Warner Bros. films