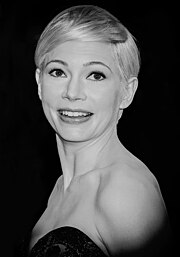

Michelle Williams (actress)

Michelle Williams | |

|---|---|

Williams in 2012 | |

| Born | Michelle Ingrid Williams September 9, 1980 Kalispell, Montana, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1993–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses | |

| Partner(s) | Heath Ledger (2004–2007) |

| Children | 3 |

| Father | Larry R. Williams |

| Awards | Full list |

Michelle Ingrid Williams (born September 9, 1980) is an American actress. Known primarily for starring in small-scale independent films with dark or tragic themes, she has received various accolades, including two Golden Globe Awards and a Primetime Emmy Award, in addition to nominations for five Academy Awards and a Tony Award.

Williams, daughter of politician and trader Larry R. Williams, began her career with television guest appearances and made her film debut in the family film Lassie in 1994. She gained emancipation from her parents at age fifteen, and soon achieved recognition for her leading role as Jen Lindley in the teen drama television series Dawson's Creek (1998–2003). This was followed by low-profile films, before having her breakthrough with the drama film Brokeback Mountain (2005), which earned Williams her first Academy Award nomination.

Williams received critical acclaim for playing emotionally troubled women coping with loss or loneliness in the independent dramas Wendy and Lucy (2008), Blue Valentine (2010), and Manchester by the Sea (2016). She won two Golden Globes for portraying Marilyn Monroe in the drama My Week with Marilyn (2011) and Gwen Verdon in the miniseries Fosse/Verdon (2019), in addition to a Primetime Emmy Award for the latter. Her highest-grossing releases came with the thriller Shutter Island (2010), the fantasy film Oz the Great and Powerful (2013), the musical The Greatest Showman (2017), and the superhero films Venom (2018) and Venom: Let There Be Carnage (2021). Williams has also led major studio films, such as Ridley Scott's crime thriller All the Money in the World (2017) and Steven Spielberg's semi-autobiographical drama The Fabelmans (2022).

On Broadway, Williams starred in revivals of the musical Cabaret in 2014 and the drama Blackbird in 2016, for which she received a nomination for the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play. She is an advocate for equal pay in the workplace. Consistently private about her personal life, Williams has a daughter from her relationship with actor Heath Ledger and was briefly married to musician Phil Elverum. She has two children with her second husband, theater director Thomas Kail.

Life and career

[edit]1980–1995: Early life

[edit]

Michelle Ingrid Williams[1] was born on September 9, 1980, in Kalispell, Montana, to Carla, a homemaker, and Larry R. Williams, an author and commodities trader.[2][3] She has Norwegian ancestry and her family has lived in Montana for generations.[4][5] Her father twice ran unsuccessfully for the United States Senate as a Republican Party nominee.[3] In Kalispell, Williams lived with her three paternal half-siblings and her younger sister, Paige.[6] Although she has described her family as "not terribly closely knit", she shared a close bond with her father, who taught her to fish and shoot, and encouraged her to become a keen reader.[7][8][9] Williams has recounted fond memories of growing up in the vast landscape of Montana.[10] When she was nine, the family moved to San Diego, California.[6] She has said of the experience, "It was less happy probably by virtue of it being my preteen years, which are perhaps unpleasant wherever you go."[10] She mostly kept to herself and was self-reliant.[11]

Williams became interested in acting at an early age when she saw a local production of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.[12] She performed in an amateur production of the musical Annie, and her parents would drive her from San Diego to Los Angeles to audition for parts. Her first screen appearance was as Bridget Bowers, a young woman who seduces Mitch Buchannon's son, Hobie, in a 1993 episode of the television series Baywatch.[7][13][14] The following year, she made her film debut in the family feature Lassie, about the bond between the titular dog and a young boy (played by Tom Guiry). Williams played the love interest of Guiry's character, which led the critic Steven Gaydos to take notice of her "winning perf".[15][16] She next took on guest roles in the television sitcoms Step by Step and Home Improvement, and appeared as the child form of Sil, an alien played in adulthood by Natasha Henstridge, in the 1995 science fiction film Species.[17][18][19]

By 1995, Williams had completed ninth grade at Santa Fe Christian Schools in San Diego.[20] She disliked going there as she did not get along well with other students. To focus on her acting pursuits, she left the school and enrolled for in-home tutoring.[11][21][22] At age fifteen, with her parents' approval, Williams filed for emancipation from them, so she could better pursue her acting career with less interference from child labor work laws.[3][23] To comply with the emancipation guidelines, she completed her high school education in nine months through correspondence.[12][22] She later regretted not getting a proper education.[22]

1996–2000: Dawson's Creek and transition to adult roles

[edit]Following her emancipation, Williams moved to Los Angeles and lived by herself in Burbank.[8][9] She said of her initial experience in the city, "There are some really disgusting people in the world, and I met some of them."[9] To support herself, she took assignments in low-budget films and commercials.[8] She had minor roles in the television films My Son is Innocent (1996) and Killing Mr. Griffin (1997), and the drama A Thousand Acres (1997), which starred Michelle Pfeiffer and Jessica Lange.[24][25][26] Williams later described her early work as "embarrassing", saying she had taken those roles merely to support herself as she "didn't have any taste [or] ideals".[8] In 1997, unhappy with the roles she was being offered, Williams collaborated with two other actors to write a script titled Blink, about prostitutes living in a Nevada brothel, which despite being sold to a production company was never made.[27][28] Having learned to trade under her father's guidance, a seventeen-year-old Williams entered the Robbins World Cup Championship, a futures trading contest; with a return of 1,000%, she became the first female to win the title and the third-highest winner of all time (her father ranks first).[29][30][31]

In 1998, Williams began starring in the teen drama television series Dawson's Creek, created by Kevin Williamson and co-starring James Van Der Beek, Katie Holmes, and Joshua Jackson. The series aired for six seasons from January 1998 to May 2003 and featured her as Jen Lindley, a precocious New York-based teenager who relocates to the fictional town of Capeside. The series was shot in Wilmington, North Carolina, where she lived for the six years of filming.[32] Reviewing the first season for The New York Times, Caryn James called it a soap opera that was "redeemed by intelligence and sharp writing" but found Williams to be "too earnest to suit this otherwise shrewdly tongue-in-cheek cast".[33] Ray Richmond of Variety labeled it "an addictive drama with considerable heart" and considered all four leads appealing.[34] The series was a ratings success and raised Williams's profile.[9][32] Her first film release since the debut of Dawson's Creek was the Jamie Lee Curtis-starring slasher picture Halloween H20: 20 Years Later (1998)—the seventh installment in the Halloween film series—in which she played one of several teenagers traumatized by the murderer Michael Myers.[35] It grossed $55 million domestically against its $17 million budget.[36]

Williams credited Dawson's Creek as "the best acting class", but also admitted to not having fully invested herself in the show as "my taste was in contradiction to what I was doing every single day."[17][27][37] She would film the series for nine months each year and spend the remaining time playing against type in independent features, which she considered a better fit for her personality.[28][37] She said the financial stability of a steady job empowered her to act in such films.[38] Williams found her first such role in the comedy Dick (1999), a parody of the Watergate scandal, in which she and Kirsten Dunst played teenagers obsessed with Richard Nixon.[8][28] Praising the film's political satire, Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly credited both actresses for playing their roles with "screwball verve".[39] Dick failed to recoup its $13 million investment.[40] In the same year Williams played a small part in But I'm a Cheerleader, a satirical comedy about conversion therapy.[41]

Keen to play challenging roles in adult-oriented projects, Williams spent the summer of 1999 starring in an off-Broadway play titled Killer Joe.[42][43] Written by Tracy Letts, it is a black comedy about a dysfunctional family who kills their matriarch for insurance money; she was cast as the family's youngest daughter. The production featured gruesome violence and required Williams to perform a nude scene.[7] Her socially conservative parents were displeased with it, but she said she found it "cathartic and freeing".[7][28][44] Her next role was in the HBO television film If These Walls Could Talk 2 (2000), a drama about three lesbian couples in different time periods. Williams signed on to the project after ensuring that a sex scene with co-star Chloë Sevigny was pertinent to the story and not meant to titillate.[44] In a mixed review of the film, Ken Tucker criticized Williams for overplaying her character's eagerness.[45] When asked about playing a series of sexual roles, she stated, "I don't think of any of them as sexy, hot girls. They were just defined at an early age by the fact that others saw them that way."[9] She subsequently made an effort to play roles that were not sexualized.[7]

2001–2005: Independent films and Brokeback Mountain

[edit]The British film Me Without You (2001), about an obsessive female friendship, starred Williams and Anna Friel. Williams played Holly, an insecure bibliophile, a part that came close to her personality.[9] The writer-director Sandra Goldbacher was initially reluctant to cast an American in a British part but was impressed by Williams's self-deprecating humor and a "European stillness".[9] Roger Ebert praised Williams's British accent and found her to be "cuddly and smart both at once".[46] Williams returned to the stage the following year in a production of Mike Leigh's farce Smelling a Rat.[47] Her part, that of a scatterbrained teenager exploring her sexuality, led Karl Levett of Backstage to label her "a first-class creative comedienne".[48] She played a supporting role in the Christina Ricci-starring Prozac Nation, a drama about depression based on Elizabeth Wurtzel's memoir.[49]

Dawson's Creek completed its run in 2003, and Williams was satisfied with how it had run its course. She relocated to New York City soon after.[50] She had supporting parts in two art-house films that year, the drama The United States of Leland and the comedy-drama The Station Agent. In the former, starring Ryan Gosling, she played the grieving sister of a murdered boy; it was described by The Globe and Mail's Liam Lacey as "neither an insightful nor well-made film".[51] The Station Agent, about a lonely dwarf (played by Peter Dinklage), featured Williams as a librarian who develops an attraction towards him. Critically acclaimed, the film's cast was nominated for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast.[52][53] On stage, Williams played Varya in a 2004 production of Anton Chekhov's drama The Cherry Orchard, alongside Linda Emond and Jessica Chastain, at the Williamstown Theatre Festival.[54] The theater critic Ben Brantley credited her for "cannily play[ing] her natural vibrancy against the anxiety that has worn the young Varya into a permanent high-strung sullenness."[55]

German filmmaker Wim Wenders wrote the film Land of Plenty (2004), which investigates anxiety and disillusionment in a post-9/11 America, with Williams in mind.[56] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times praised Wenders's thoughtful examination of the subject and noted Williams's screen appeal.[57] She received an Independent Spirit Award for Best Female Lead nomination for the film.[58] The actor next appeared in Imaginary Heroes, a drama about a family coping with their son's suicide, and played an impressionable young woman fixated on mental health in the period film A Hole in One.[59][60] Williams returned to the comedy genre with The Baxter, in which she played a geeky secretary. The film received negative reviews; Wesley Morris of The Boston Globe wrote, "Only when Williams is around does the movie seem human, true, and funny. Even in her slapstick, there's pain."[61][62] As with her other films during this period, it received only a limited release and was not widely seen.[63][64]

Her film breakthrough came later in 2005 when Williams appeared in Ang Lee's drama Brokeback Mountain, about the romance between two men, Ennis and Jack (played by Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal, respectively). Impressed with her performance in The Station Agent, the casting director Avy Kaufman recommended Williams to Lee. He found a vulnerability in her and cast her as Alma, the wife of Ennis, who discovers her husband's homosexual infidelity.[65] The actor was emotionally affected by the story and, despite her limited screen time, she was drawn to the idea of playing a woman constricted by the social mores of the time.[21] Deeming her the standout among the cast, Ed Gonzalez of Slant Magazine commended Williams for "fascinatingly spiking [Alma's] unspoken resentment for her sham of a marriage with a hint of compassion for Ennis's secret suffering".[66] Brokeback Mountain proved to be her most widely seen film to that point, grossing $178 million against its $14 million budget, and she received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress.[67][68] Williams began dating Ledger while working on the film.[21] The couple cohabited in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn,[69] New York, and in 2005, she gave birth to their daughter Matilda.[65]

2006–2010: Work with auteurs

[edit]Williams had two film releases in 2006. She first featured opposite Paul Giamatti in the drama The Hawk Is Dying.[8] Five months after giving birth to her daughter, she returned to work on Ethan Hawke's directorial venture The Hottest State, based on his own novel. Leslie Felperin of Variety found her role too brief.[70] Following the awards-season success of Brokeback Mountain, Williams was unsure of what to do next. After six months of indecision, she agreed to a small part in Todd Haynes's I'm Not There (2007), a musical inspired by the life of Bob Dylan.[71] She was then drawn to the part of an enigmatic seductress named S in the 2008 crime thriller Deception.[8][72] The film, which co-starred Hugh Jackman and Ewan McGregor, was considered by critics to be middling and predictable.[73] In her next release, Incendiary, based on Chris Cleave's novel of the same name, Williams reteamed with McGregor to play a woman whose family is killed in a terrorist attack. A reviewer for The Independent called the film "sloppy" and added that Williams deserved better.[74]

Williams's two other releases of 2008 were better received. The screenwriter Charlie Kaufman was impressed with her comic timing in Dick and thus cast her in his directorial debut Synecdoche, New York, an ensemble experimental drama headlined by Philip Seymour Hoffman.[56] It was a box office bomb and polarized critics, although Roger Ebert named it the best film of the decade.[75][76][77] Two days after finishing work on Synecdoche, New York, Williams began filming Kelly Reichardt's Wendy and Lucy, playing the part of a poor and lonesome young woman traveling with her dog and looking for employment.[78] With a shoestring budget of $300,000, the film was shot on location in Portland, Oregon, with a largely volunteer crew.[78] Williams had just separated from Ledger and was relieved for the anonymity the project provided.[56][79] She was pleased with Reichardt's minimalistic approach and identified with her character's self-sufficiency and fortitude.[78][80] Sam Adams of the Los Angeles Times considered her performance to be "remarkable not only for its depth but for its stillness" and Mick LaSalle commended her for effectively conveying a "lived-in sense of always having been close to the economic brink".[81][82]

Williams was filming in Sweden for her next project, Mammoth (2009), when news broke that Ledger had died of an accidental intoxication from prescription drugs.[32][56] Although Williams continued filming, she later said, "It was horrible. I don't remember most of it."[7] In her first public statement, a week after his death, she expressed her heartbreak and described Ledger's spirit as surviving in their daughter.[83] She attended his memorial and funeral services later that month.[84]

Mammoth was directed by the Swedish director Lukas Moodysson and featured Williams and Gael García Bernal as a couple dealing with issues stemming from globalization. Her role was that of an established surgeon, a part she deemed herself too young to logically play.[71] In the same year, she co-starred with Natalie Portman in a Roman Polanski-directed faux perfume commercial called Greed.[85] For her next project, Martin Scorsese cast her opposite Leonardo DiCaprio in the psychological thriller Shutter Island. Based on Dennis Lehane's novel, it featured her as a depressed housewife who drowns her own children. The high-profile production marked a departure for her, and she found it difficult to adjust to the slower pace of filming.[86] In preparation, she read case studies on infanticide.[56] After finishing work on the film in 2008, Williams admitted that playing a series of troubled women coupled with her own personal difficulties had taken an emotional toll. She took a year off work to focus on her daughter.[56][86] Shutter Island was released in 2010 and was a commercial success, earning over $294 million worldwide.[87]

Williams had first read the script for Derek Cianfrance's romantic drama Blue Valentine at age 21. When funding came through after years of delay, she was reluctant to accept the offer as filming in California would take her away from her daughter for too long.[88][89] Keen to have her in the film, Cianfrance decided to shoot it near Brooklyn, where Williams lived.[89] Co-starring Ryan Gosling, Blue Valentine traces the tribulations faced by a disillusioned married couple. Before production began, Cianfrance had Williams and Gosling live together for a month on a stipend that matched their characters' income. This exercise led to conflicts between them, which proved conducive for filming their characters' deteriorating marriage.[90] On set, she and Gosling practiced method acting by improvising several scenes.[43] The film premiered at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival to critical acclaim.[91] The New York Times's reviewer A. O. Scott found Williams to be "heartbreakingly precise in every scene" and commended the duo for being "exemplars of New Method sincerity, able to be fully and achingly present every moment on screen together".[92] She received Academy Award and Golden Globe Award nominations for Best Actress.[93][94]

In her final film project of 2010, she reunited with Kelly Reichardt for the western Meek's Cutoff. Set in 1845, it is based on an ill-fated historical incident on the Oregon Trail, in which the frontier guide Stephen Meek led a wagon train through a desert. Williams starred as one of the passengers on the wagon, a feisty young mother who is suspicious of Meek. In preparation, she took lessons on firing a gun and learned to knit.[95][96] Filming in extreme temperatures in the desert proved arduous for her, though she enjoyed the challenge.[96] Writing for The Arizona Republic, Bill Goodykoontz praised the subtlety both in the film and in Williams's performance.[97]

2011–2016: My Week with Marilyn and Broadway

[edit]

In 2011, Williams portrayed Marilyn Monroe in My Week with Marilyn, a drama depicting the troubled production of the 1957 comedy The Prince and the Showgirl, based on accounts by Colin Clark, who worked on the latter film. Initially skeptical about playing Monroe, as she had little in common with her looks or personality, Williams spent six months researching her by reading biographies, diaries and notes, and studying her posture, gait, and mannerisms.[98][99] She also gained weight for the part, bleached her hair blonde, and on days of filming, underwent over three hours of makeup.[100] She sang three songs for the film's soundtrack and recreated a performance of Monroe singing and dancing to "Heat Wave".[101][102] Roger Ebert considered Williams's performance to be the film's prime asset and credited her for successfully evoking multiple aspects of Monroe's personality.[103] Peter Travers opined that despite not physically resembling Monroe, she had "with fierce artistry and feeling [illuminated] Monroe's insights and insecurities about herself at the height of her fame".[104] For her portrayal, she won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress and received a second consecutive Oscar nomination.[105]

In Sarah Polley's romance Take This Waltz (2011), co-starring Seth Rogen and Luke Kirby, Williams played a married writer attracted to her neighbor. Though the actor considered it to be a light-hearted film, Jenny McCartney of The Daily Telegraph found a darker undertone to it and favorably compared its theme to that of Blue Valentine.[106][107] To play a part that would appeal to her daughter, Williams starred as Glinda in Sam Raimi's fantasy picture Oz the Great and Powerful (2013). Based on the Oz children's books, it served as a prequel to the 1939 classic film The Wizard of Oz.[6] It marked her first appearance in a film involving special effects and she credited Raimi for making her comfortable with the process.[108] The film earned over $490 million worldwide to rank as one of her highest-grossing releases.[109] Suite Française, a period drama that Williams filmed in 2013, was released in a few territories in 2015 but was not theatrically distributed in America.[110] She later admitted to being displeased with how the film turned out, adding that she found it hard to predict the quality of a project during production.[111] Eager to work in a different medium and finding it tough to obtain film roles that enabled her to maintain her parental commitments, Williams spent the next few years working on the stage.[112][113]

Her desire to star in a musical led Williams to the role of Sally Bowles in a 2014 revival of Cabaret, which was staged at Studio 54 and marked her Broadway debut.[114] Jointly directed by Sam Mendes and Rob Marshall, it tells the story of a free-spirited cabaret performer (Williams) in 1930s Berlin during the rise of the Nazi Party. Before production began, she spent four months privately rehearsing with music and dance coaches. She read the works of Christopher Isherwood, whose novel Goodbye to Berlin inspired the musical, and visited Berlin to research Isherwood's life and inspirations.[115] Her performance received mixed reviews;[116] Jesse Green of Vulture praised her singing and commitment to the role, but Newsday's Linda Winer thought her portrayal lacked depth.[117][118] The rigorousness of the assignment led Williams to consider Cabaret her toughest project.[119]

Challenged by her work on Cabaret, Williams was eager to continue working on the stage.[112][120] She found a part in a 2016 revival of the David Harrower play Blackbird. Set entirely in the lunchroom of an office, it focuses on a young woman (Williams), who confronts a much older man (played by Jeff Daniels) for having sexual relations with her when she was twelve years old. Williams, who had not seen previous stagings of the play, was drawn to the ambiguity of her role and found herself unable to detach from it after each performance.[121] Hilton Als of The New Yorker considered her "daring and nonjudgmental embodiment of her not easily assimilable character" to be the production's highlight.[122] She received a Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play nomination for Blackbird.[123]

Williams returned to film in 2016 with supporting roles in two small-scale dramas, Certain Women and Manchester by the Sea.[119] The former marked her third collaboration with Kelly Reichardt and told three interconnected narratives based on the short stories of Maile Meloy. As with their previous collaborations, the film featured minimal dialogue and required Williams to act through silences.[5] Kenneth Lonergan's Manchester by the Sea starred Casey Affleck as Lee, a depressed man who separates from his wife, Randi (Williams), following the tragic death of their children. Williams agreed to the project to work with Lonergan, whom she admired, and despite the film's bleakness she found a connection with her character's desire to reclaim her life in the face of tragedy.[119][5] In preparation, she visited Manchester to interview local mothers about their lives and worked with a dialect coach to speak in a Massachusetts accent.[119][124] Several critics hailed Williams's climactic monologue, in which Randi confronts Lee, as the film's highlight; Justin Chang termed it an "astonishing scene that rises from the movie like a small aria of heartbreak."[125][126] She received her fourth Oscar nomination, her second in the Best Supporting Actress category.[127]

2017–present: Mainstream films, Fosse/Verdon, and marriages

[edit]

Following a brief appearance in Todd Haynes's drama Wonderstruck (2017),[128] Williams appeared in the musical The Greatest Showman. Inspired by P. T. Barnum's creation of the Barnum & Bailey Circus, the film featured her as Charity, the wife of Barnum (played by Hugh Jackman).[129] She likened her character's joyful disposition to that of Grace Kelly,[112] and she sang two songs for the film's soundtrack.[130] The film emerged as one of her most successful, earning over $434 million worldwide.[131]

Ridley Scott's crime thriller All the Money in the World (2017) was Williams's first leading role in film since 2013.[132] She starred as Gail Harris, whose son, John Paul Getty III, is kidnapped for ransom. She considered it a major opportunity, since she had not headlined a big-budget Hollywood production before.[133] A month prior to the film's release, Kevin Spacey, who originally played J. Paul Getty, was accused of sexual misconduct; he was replaced with Christopher Plummer, and Williams reshot her scenes days before the release deadline.[134][135] The critic David Edelstein bemoaned that Williams's work had been overshadowed by the controversy and went on to commend her "marvelous performance", noting how she conveyed her character's grief through "the tension in her body and intensity of her voice".[136] She received her fifth Golden Globe nomination for the role.[137] It was later reported that her co-star Mark Wahlberg had been paid $1.5 million to Williams's $1,000 for the reshoots, which sparked a discourse on gender pay gap amongst Hollywood.[138]

In 2018, Williams married the musician Phil Elverum in a secret ceremony in the Adirondack Mountains.[139] Her first film role of the year was as a haughty but insecure executive in the Amy Schumer-starring comedy I Feel Pretty, which satirizes body image issues among women. The comedic role, which required her to speak in a high-pitched voice, led Peter Debruge of Variety to term it "the funniest performance of her career".[140][141] The film was a modest box office success.[142] In a continued effort to work on different genres, Williams played Anne Weying in the superhero film Venom, co-starring Tom Hardy as the titular antihero.[139][143] Influenced by the MeToo movement, she provided off-screen inputs regarding her character's wardrobe and dialogue, but the critic Peter Bradshaw found it to be "an outrageously boring and submissive role".[143][144] Venom earned over $855 million worldwide, making it the highest-grossing film in which Williams has appeared.[145]

Williams returned to the Sundance Film Festival in 2019 with After the Wedding, a remake of Susanne Bier's Danish film of the same name, in which she and Julianne Moore played roles portrayed by men in the original.[146] Benjamin Lee of The Guardian considered the low-key part to be a better fit than her previous few roles.[147] Fosse/Verdon, an FX miniseries about the troubled personal and professional relationship between Bob Fosse and Gwen Verdon, marked her first leading role on television since Dawson's Creek.[148] Williams felt her Broadway run in Cabaret helped prepare her to portray Verdon.[149] She also served as an executive producer on the series, and was pleased not to have to negotiate to receive equal pay to her co-star Sam Rockwell.[139] John Doyle of The Globe and Mail lauded Williams for "play[ing] Verdon with a wonderfully controlled sense of the woman's total commitment to her art and craft while always standing on the edge of an emotional abyss."[150] She won the Primetime Emmy Award and Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Television Miniseries.[151][152]

Elverum and Williams filed for divorce in April 2019;[153][154] by November 2019, it was reported that they were no longer married.[154] She later described the marriage as a "mistake".[155] Later in 2019, Williams became engaged to the theater director Thomas Kail, with whom she worked on Fosse/Verdon;[156] they married in March 2020.[157] She gave birth to their son later in 2020 and another child in 2022.[157][158]

In 2021, Williams reprised the role of Anne Weying in the superhero sequel Venom: Let There Be Carnage.[159] It received mixed reviews, but grossed over $500 million worldwide.[160][161] In her fourth collaboration with Kelly Reichardt, Williams starred in the drama Showing Up (2022). For her role as a sculptor in it, she shadowed the artist Cynthia Lahti.[162] Tim Robey of The Independent opined that Williams "thrives more intelligently than ever under Reichardt's watch here".[163] Later in 2022, Williams starred in The Fabelmans, Steven Spielberg's semi-autobiographical film about his childhood, in which she played Mitzi Fabelman, a character inspired by his mother.[164] Spielberg had her in mind for the part after seeing her performance in Blue Valentine; in preparation, she heard recordings and watched home movies of his childhood.[165][162] The film received critical acclaim;[166] Pete Hammond of Deadline Hollywood labeled Williams "gut-wrenchingly great" and Kyle Buchanan of The New York Times wrote that she "really goes for it, attacking this part like someone who knows she’s been handed her signature role".[167][165] She received further Best Actress nominations at the Golden Globe and Academy Award ceremonies.[168][169]

After filming The Fabelmans, Williams took a two-and-a-half year break from acting.[170] In 2023, she was enlisted by singer Britney Spears to narrate the audiobook version of her memoir The Woman in Me.[171] A clipping from the audiobook, in which Williams imitates Justin Timberlake speaking in "blaccent" went viral on social media.[172] She will return to acting with Dying for Sex, an FX miniseries based on the podcast of the same name, about a married woman with cancer who begins to explore her sexuality.[170]

Public image and acting style

[edit]Describing Williams's off-screen persona, Debbie McQuoid of Stylist magazine wrote in 2016 that she is "predictably petite but her poise and posture make her seem larger than life".[113] The journalist Andrew Anthony has described her as unpretentious, low-key, and unassuming.[86] Charles McGrath of The New York Times considers her to be unlike a movie star and has called her "shy, earnest, thoughtful, and [...] a little wary of publicity".[114] Williams has spoken about how she tries to balance her desire to be private and her wish to use her celebrity to speak out on issues such as sexism, gender pay gap, and sexual harassment.[173] On Equal Pay Day in 2019, she utilized the pay gap controversy surrounding her film All the Money in the World to deliver an address at the United States Capitol urging passage of the Paycheck Fairness Act.[174] During her 2020 Golden Globe acceptance speech for Fosse/Verdon, she advocated for the importance of women's and reproductive rights.[175][176]

In the aftermath of her ex-partner Heath Ledger's death in January 2008, Williams became the subject of intense media scrutiny and was frequently stalked by paparazzi.[86][177] She disliked the attention, saying it interfered with her work and made her self-conscious.[10][178] Although reluctant to publicly discuss her romantic relationships, Williams was forthright in expressing her grief over Ledger's death, saying it had left a permanent hole in both her and her daughter's life.[3][179] She has since affirmed her determination to look after her daughter in spite of her difficulties as a single parent.[112] In 2018, she opened up about her relationship and marriage to Phil Elverum to provide grieving women with inspiration.[139]

Williams prefers acting in small-scale independent films to high-profile, mainstream productions, finding this to be "a very natural expression of [her] interest".[114][180] Elaine Lipworth of The Daily Telegraph has identified a theme of "dark, often tragic characters" in her career, and Katie O'Malley of Elle writes that she specializes in "playing strong, independent and forthright female characters".[6][181] Susan Dominus of The New York Times considers her to be a "tragic embodiment of grief, in life and in art".[155] Regarding her selection of roles, Williams has said she is drawn toward "people's failings, blind spots, inconsistencies".[6] She believes that her own unconventional adolescence informs these choices.[170] She agrees to a project on instinct, calling it an "un-thought out process".[181] Describing her acting process in 2008, she stated:

Acting sometimes reminds me of therapy in that the more you talk about a traumatic or profound event, the more it loses its emotional tension. [The trick is] to live in so much mystery, to rely on a feeling, an instinct, on faith, really, that everything I need is already inside me, and best I just don't block the exit.[56]

Erica Wagner of Harper's Bazaar has praised Williams for combining "startlingly emotional performance with a sense of groundedness" and the critic David Thomson opines that she "can play anyone, without undue glamour or starriness".[173][182] Adam Green of Vogue considers Williams's ability to reveal "the inner lives of her characters in unguarded moments" to be her trademark, and credits her for not "trading on her sex appeal" despite her willingness to perform nude scenes.[98] Her Manchester by the Sea director Kenneth Lonergan has stated that her versatility allows her to be "transformed, in her whole person" by the role she plays.[183] Dominus also believes that she physically transforms herself "as if all her molecules have fallen apart and been reassembled to create a slightly different version of herself, the material attributes the same but the essence transformed".[155] Describing her career in 2016, Boris Kachka of Elle termed it a metamorphosis from "celebrated indie ingenue to muscular, chameleonic movie star".[179] In a 2022 readers' poll by Empire magazine, Williams was voted one of the 50 greatest actors of all time.[184] The magazine attributed her success to playing "damaged, broken and hurt characters with such heartbreaking sensitivity, you can never see the seams".[184]

The saffron Vera Wang gown Williams wore to the 78th Academy Awards in 2006 is regarded as one of the greatest Oscar dresses of all time.[185][186] Williams has featured as the brand ambassador for the fashion label Band of Outsiders and the luxury brand Louis Vuitton.[187][188] She has appeared in several advertisement campaigns for the latter company, and in 2015, she starred alongside Alicia Vikander in their short film named The Spirit of Travel.[189]

Acting credits and awards

[edit]According to the review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes and the box-office site Box Office Mojo, Williams's most critically acclaimed and commercially successful films are The Station Agent (2003), Brokeback Mountain (2005), Wendy and Lucy (2008), Blue Valentine (2010), Shutter Island (2010), Meek's Cutoff (2010), My Week with Marilyn (2011), Oz the Great and Powerful (2013), Manchester by the Sea (2016), Certain Women (2016), The Greatest Showman (2017), Venom (2018), Venom: Let There Be Carnage (2021), and The Fabelmans (2022).[64][190] Among her stage roles, she has appeared on Broadway in revivals of Cabaret in 2014 and Blackbird in 2016.[112]

Williams has received five Academy Award nominations: Best Supporting Actress for Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Manchester by the Sea (2016); and Best Actress for Blue Valentine (2010), My Week with Marilyn (2011), and The Fabelmans (2022).[191] She won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Comedy or Musical for My Week with Marilyn (2011) and Best Actress – Miniseries or Television Film for Fosse/Verdon (2019); she has been nominated five more times: Best Actress in a Drama for Blue Valentine (2010), All the Money in the World (2017), and The Fabelmans (2022); and Best Supporting Actress for Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Manchester by the Sea (2016).[192] Williams also won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Limited Series or Movie for Fosse/Verdon (2019) and received a nomination for the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play for Blackbird.[151][123]

References

[edit]- ^ Cunningham, John M. (December 16, 2024). "Michelle Williams". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

Also known as: Michelle Ingrid Williams

- ^ "Michelle Williams". Biography.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Bennetts, Leslie (February 2011). "Belle Michelle". Marie Claire: 124–128. ASIN B004JEJYLE.

- ^ Vida, Vendela (May 2011). "Michelle Williams". Interview. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c Berman, Eliza (November 2, 2016). "Michelle Williams on the 'Bravest Human Being' She's Ever Played". Time. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Lipworth, Elaine (February 24, 2013). "Oz the Great and Powerful: Michelle Williams interview". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Heath, Chris (January 17, 2012). "Some Like Her Hot". GQ. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hartman, Eviana (June 13, 2014). "Flashback Friday: My cover with Michelle". Nylon. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Greenberg, James (June 23, 2002). "Up and Coming; Growing Up Fast, on Screen and Off". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c Illey, Chrissy (February 19, 2017). "The Interview: Michelle Williams, Oscar-nominated for Manchester by the Sea". The Times. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Michelle Williams: What's the matter with Michelle?". The Independent. November 23, 2001. Archived from the original on November 24, 2001.

- ^ a b Galloway, Stephen; Guider, Elizabeth (December 8, 2008). "Oscar Roundtable: The Actresses". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012.

- ^ Boardman, Madeline (August 12, 2016). "18 Stars You Forgot Were on 'Baywatch'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Baywatch – Season 4, Episode 1: Race Against Time (1)". TV.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016.

- ^ Crossan, Ashley (July 22, 2014). "14-Year-Old Michelle Williams is Adorable on the Set of 'Lassie'". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016.

- ^ Gaydos, Steven (July 21, 1994). "Lassie". Variety. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Teeman, Tim (January 26, 2011). "Michelle Williams is kinda blue". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ Harris, Scott (March 4, 2013). "Watch Michelle Williams on 'Home Improvement' in 1995". MTV. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ James, Caryn (July 7, 1995). "Film Review; Singles Bars And Single Half-Aliens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016.

- ^ Peterson, Todd (March 3, 2006). "Michelle Williams Snubbed by Former School". People. Archived from the original on March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Bunbury, Stephanie (January 15, 2006). "The mother lode". The Age. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c Gross, Terry (February 17, 2012). "Michelle Williams: The Fresh Air Interview". NPR. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Michelle Williams' emancipation prompted by Hollywood headlines". San Francisco Chronicle. January 11, 2011. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011.

- ^ Everett, Todd (May 6, 1996). "My Son is Innocent". Variety. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ Tibbs, Kathe; Peterson, Biff L. (1999). They Don't Wanna Wait: The Stars of Dawson's Creek. ECW Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-55022-389-7. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ "A Thousand Acres (1997)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "Michelle Ma Belle". Wonderland. March 2008. Archived from the original on March 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Michelle Williams, Naked Angel". Paper. June 30, 1999. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ Jenkins, Christine (January 26, 2011). "Here's How Actress Michelle Williams Won The World Cup Of Futures Trading Award at Age 17". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013.

- ^ "Standings". World Cup Trading Championships. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ "Actress takes top prize in long-running trading competition". Modern Trader. May 6, 2014. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c Singer, Sally (October 2009), "A Field Guide to Getting Lost", Vogue, no. 8449, p. 204

- ^ James, Caryn (January 20, 1998). "Television Review; Young, Handsome and Clueless in Peyton Place". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ Richmond, Ray (January 19, 1998). "Dawson's Creek". Variety. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- ^ Graham, Bob (August 5, 1998). "Sweet Revenge: Jamie Lee Curtis returns to face down her killer brother in 'Halloween: H20'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017.

- ^ "Halloween: H20". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "Finding herself atop a 'Mountain'". Los Angeles Times. February 15, 2006. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006.

- ^ "Michelle Williams". Variety. December 11, 2005. Archived from the original on January 14, 2018.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (August 13, 1999). "Movie Review: 'Dick'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Dick (1999)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ Atwell, Elaine (September 25, 2015). "Sapphic Cinema: "But I'm a Cheerleader"". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Brodesser, Claude (April 9, 1999). "Off Broadway's 'Killer Joe' makes room for Williams". Variety. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Gross, Terry (April 14, 2011). "Going West: The Making Of 'Meek's Cutoff'". NPR. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Bonin, Liane (July 29, 1999). "Michelle Williams bares all for her art". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018.

- ^ Tucker, Ken (March 3, 2000). "If These Walls Could Talk 2 (2000)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 16, 2002). "Film Review; Best Friends Who Are Also Worst Enemies Struggle in a Web of Emotions". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018.

- ^ Ehren, Christine (April 8, 2002). "New Group Is Smelling a Rat with Michelle Williams May 7 – June 16". Playbill. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016.

- ^ Levett, Karl (June 19, 2002). "Smelling a Rat". Backstage. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (September 10, 2001). "Review: 'Prozac Nation'". Variety. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016.

- ^ Lynch, Jason (May 19, 2003). "Departing Shots". People. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018.

- ^ Lacey, Liam (April 9, 2004). "Review: The United States of Leland". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on May 3, 2004.

- ^ "The Station Agent". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017.

- ^ "'Mystic River', 'Station Agent' top SAG award nominations". The Seattle Times. January 16, 2004. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012.

- ^ Simonson, Robert (August 11, 2004). "Linda Emond and Michelle Williams Wander The Cherry Orchard at Williamstown, Aug. 11–22". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (August 17, 2004). "Theatre Review; Conflicting Impulses Of Chekhov's Last Play". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lim, Dennis (September 7, 2008). "For Michelle Williams, It's All Personal: Filmmakers Love Her Work, While the Public Remembers Her Heath Ledger Connection". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (November 11, 2005). "Land of Plenty". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2007.

- ^ ""Half Nelson", "Little Miss Sunshine" Top Spirit Award Nominations". IndieWire. November 28, 2006. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (February 25, 2005). "Details etch a portrait of family grief over suicide". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 14, 2005.

- ^ Stevens, Dana (May 6, 2005). "Film in Review; 'A Hole in One'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015.

- ^ "The Baxter (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. August 26, 2005. Archived from the original on September 18, 2011.

- ^ Morris, Wesley (September 16, 2005). "'The Baxter' is snappy but self-consciously hip". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 11, 2007.

- ^ "The Baxter". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011.

- ^ a b "Michelle Williams Movie Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 31, 2016.

- ^ a b Valby, Karen (January 6, 2006). "Michelle Williams climbs Brokeback Mountain". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ed (November 15, 2005). "Brokeback Mountain". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Brokeback Mountain". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011.

- ^ "List of Academy Award Winners and Nominees". The New York Times. 2006. Archived from the original on May 19, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Alex (September 30, 2007). "Brooklyn's Fragile Eco-System". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Felperin, Leslie (September 2, 2006). "The Hottest State". Variety. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Roston, Tom (November 18, 2008). "Michelle Williams opens up about new work". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 14, 2018.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe (April 25, 2008). "Movie review: 'Deception' sizzles and fizzles". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017.

- ^ "Deception (2008)". Rotten Tomatoes. April 25, 2008. Archived from the original on April 6, 2010.

- ^ Hanks, Robert (October 24, 2008). "Incendiary (15)". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009.

- ^ "Synecdoche, New York". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011.

- ^ "Synecdoche, New York". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 30, 2009). "The Best Films of the Decade". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Ella (December 17, 2008). "Michelle Williams Finds a Safe Haven With Outsider Director Kelly Reichardt on Wendy and Lucy". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ Triggs, Charlotte (September 2, 2007). "Heath Ledger and Michelle Williams Split". People. Archived from the original on September 10, 2011.

- ^ Nicholas, Michelle (December 9, 2008). "Michelle Williams says 'Wendy and Lucy' role a gift". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014.

- ^ Adams, Sam (December 12, 2008). "Review: 'Wendy and Lucy'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (January 30, 2009). "Movie review: 'Wendy and Lucy' is eerily timely". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 14, 2018.

- ^ "Michelle Williams Breaks Silence on Heath's Death". People. February 1, 2008. Archived from the original on March 29, 2011.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (February 9, 2008). "Heath Ledger Remembered at Funeral; Michelle Williams Takes A Tearful Ocean Swim in His Honor". MTV. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012.

- ^ "MOCA gets its hands on Francesco Vezzoli's 'Greed', starring Natalie Portman and Michelle Williams". Los Angeles Times. March 18, 2011. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Anthony, Andrew (March 8, 2009). "'I don't want any more paparazzi outside my door'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016.

- ^ "Shutter Island". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016.

- ^ Riley, Jenelle (December 9, 2010). "Scenes From a Marriage". Backstage. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Shone, Tom (January 10, 2011). "Blue Valentine: Michelle Williams interview". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018.

- ^ Hall, Katy (February 7, 2011). "Blue Valentine : How Derek Cianfrance Destroyed Michelle Williams and Ryan Gosling's Marriage". HuffPost. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017.

- ^ Kennedy, Lisa (January 13, 2011). "Colorado-reared "Blue Valentine" director is thankful film took 12 years to make". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (December 28, 2010). "Chronicling Love's Fade to Black". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012.

- ^ "Nominations and Winners – 2010". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012.

- ^ "Nominees for the 83rd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012.

- ^ Cwelich, Lorraine (April 6, 2011). "Michelle Williams on Meek's, Marilyn & 30". Elle. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Applebaum, Stephen (2011). "Interview: Michelle Williams". Stylist. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Goodykoontz, Bill (May 26, 2011). "'Meek's Cutoff', 4 stars". The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Green, Adam (September 13, 2011). "Michelle Williams: My Week with Michelle". Vogue. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013.

- ^ Setoodeh, Ramin (October 30, 2011). "Michelle Williams on My Week With Marilyn Monroe". Newsweek. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Gardner, Jessica (December 7, 2011). "How Michelle Williams Found the Heart of Marilyn Monroe". Backstage. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Whip, Glenn (February 9, 2017). "Michelle Williams talks about her year with Marilyn". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (October 25, 2011). "Michelle Williams Sings On 'My Week With Marilyn' Soundtrack; Also Dean Martin, Nat King Cole & More". IndieWire. Archived from the original on June 16, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 21, 2011). "My Week With Marilyn". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Travers, Peter (November 21, 2011). "My Week with Marilyn". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (February 12, 2012). "Oscars Q&A: Michelle Williams On How She Morphed into Marilyn Monroe". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015.

- ^ Lewis, Tim (August 5, 2012). "Michelle Williams: 'Being embarrassed in public is the worst thing I can imagine'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ McCartney, Jenny (August 21, 2012). "Take This Waltz, Seven magazine review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Radish, Christina (March 2, 2013). "Michelle Williams and Rachel Weisz Talk Oz the Great and Powerful Perks of Playing Witches, Doing Wire Work for their Fight Scene and Costumes". Collider. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ "Oz The Great and Powerful (2013)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016.

- ^ Winfrey, Graham (May 11, 2017). "'Suite Française': The Real Reason Why the Weinstein Company's WWII Drama Ended Up at Lifetime". IndieWire. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017.

- ^ Dunn, Jamie (January 3, 2017). "Michelle Williams: "It's unnatural to see yourself large on a screen"". The Skinny. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Bennetts, Leslie (January 23, 2017). "Through It All, Michelle Williams Is Having a Blast". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ a b McQuoid, Debbie (December 9, 2016). "Michelle Williams on her new film, dealing with criticism and why she's an expert at napping". Stylist. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c McGrath, Charles (March 27, 2014). "Life Is an Audition". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Green, Adam (March 31, 2014). "Michelle Williams Is Back on Broadway—and Starring in Cabaret". Vogue. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ "Michelle Williams gets mixed reviews in Broadway revival of Cabaret". BBC News. April 25, 2014. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015.

- ^ Green, Jesse (April 24, 2014). "Theater Review: Michelle Williams and Alan Cumming Come (Back) to the Cabaret". Vulture. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Winer, Linda (April 24, 2014). "'Cabaret' review: Alan Cumming is still dangerous". Newsday. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Hirschberg, Lynn (February 8, 2017). "Michelle Williams, Star of Manchester by the Sea, Also Doesn't Want to Watch Sad Movies". W. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Green, Adam (February 5, 2016). "Michelle Williams and Jeff Daniels Bring Blackbird's Unsettling Seduction to Broadway". Vogue. Archived from the original on July 22, 2017.

- ^ Soloski, Alexis (April 4, 2016). "Michelle Williams and Jeff Daniels on the scared, desperate tale of Blackbird". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016.

- ^ Als, Hilton (March 21, 2016). "My Old Sweetheart". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "See Full List of 2016 Tony Award Nominations". Playbill. May 3, 2016. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016.

- ^ Setoodeh, Ramin (January 23, 2016). "Sundance: Michelle Williams on How She Prepared for 'Manchester by the Sea' and 'Certain Women'". Variety. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Matthew (November 23, 2016). "A Close Look at Casey Affleck And Michelle Williams' Standout Scene In 'Manchester by the Sea'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018.

- ^ Chang, Justin (January 23, 2016). "Sundance Film Review: 'Manchester by the Sea'". Variety. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017.

- ^ Pressberg, Matt (January 24, 2017). "No, Oscar Nominee Michelle Williams Still Hasn't Seen 'Manchester by the Sea'". TheWrap. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017.

- ^ Barber, Nicholas (May 19, 2017). "Julianne Moore stars in a mystical childhood fable". BBC News. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017.

- ^ Greenblatt, Leah (December 20, 2017). "The Greatest Showman sings a shallow, shiny song". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018.

- ^ "The Greatest Showman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". iTunes (Apple Inc.). December 8, 2017. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- ^ "The Greatest Showman (2017)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017.

- ^ Buchanan, Kyle (January 10, 2018). "Michelle Williams Is Ready to Lead". Vulture. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Ellwood, Gregory (January 9, 2018). "Michelle Williams found big challenges and even bigger opportunities in 'All the Money'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr.; Hipes, Patrick (November 6, 2017). "More Kevin Spacey Shrapnel: Ridley Scott's 'All The Money In The World' Exits AFI Fest Closing Slot". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017.

- ^ Lang, Brent; Kroll, Justin (November 10, 2017). "Replacing Kevin Spacey on 'All the Money in the World' Will Cost Millions". Variety. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017.

- ^ Edelstein, David (December 20, 2017). "Christopher Plummer Is Getting Headlines for All the Money in the World, But It's Michelle Williams Who Deserves Them". Vulture. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ Vilkomerson, Sara (December 11, 2017). "All the Money in the World nabs 3 Golden Globe nods after Christopher Plummer swap". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (January 11, 2018). "'All The Money in The World' Triggers Wage Gap Debate". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Fortini, Amanda (July 26, 2018). "'I Never Gave Up on Love': Michelle Williams on Her Very Private Wedding and Very Public Fight for Equal Pay". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Matthew (April 20, 2018). "Michelle Williams Gives The Kookiest Performance Of Her Career In 'I Feel Pretty'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (April 18, 2018). "Film Review: Amy Schumer in 'I Feel Pretty'". Variety. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ "I Feel Pretty (2018)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Davids, Brian (October 1, 2018). "Why Michelle Williams Said Yes to 'Venom'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (October 3, 2018). "Venom review – Tom Hardy flames out in poisonously dull Spider-Man spin-off". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ "Venom (2018)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ Handler, Rachel (January 25, 2019). "Michelle Williams and Julianne Moore on Their 'Raw, Animalistic' After The Wedding Scene". Vulture. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (January 25, 2019). "After the Wedding review – Julianne Moore and Michelle Williams lift confused melodrama". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 25, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Drysdale, Jennifer (February 4, 2019). "Michelle Williams on Why Return to TV in 'Fosse/Verdon' Was a 'Next-Level Degree of Difficulty'". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ Fierberg, Ruthie (April 9, 2019). "16 Fosse/Verdon Secrets From Lin-Manuel Miranda, Michelle Williams, Sam Rockwell, and More". Playbill. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ Doyle, John (April 9, 2019). "Fosse/Verdon is a great, ravishing television drama about theatre, love and life". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Minutaglio, Rose (September 23, 2019). "Michelle Williams Uses Emmys Acceptance Speech To Call Out Workplace Inequality For Women Of Color". Elle. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Minutaglio, Rose (January 6, 2020). "Michelle Williams Uses Her Golden Globes Acceptance Speech To Defend A Woman's Right To Choose". Elle. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Real, Evan (April 19, 2019). "Michelle Williams and Husband Phil Elverum Split After Marrying Last Summer". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Greene, Jayson (November 12, 2019). "Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Starts Over, Again". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

[Elverum]'s not married to Williams anymore either; they quietly filed for divorce this April, after less than a year of marriage.

- ^ a b c Dominus, Susan (October 13, 2022). "Michelle Williams". The New York Times. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ Luu, Christopher (December 30, 2019). "Michelle Williams Is Engaged – and Expecting". InStyle. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Waterhouse, Jonah (June 18, 2020). "Michelle Williams Gives Birth to Her Second Child in Lockdown". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Seemayer, Zach (November 6, 2022). "Michelle Williams Talks Motherhood, Holiday Plans After Welcoming Baby No. 3". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ Alter, Ethan (August 7, 2019). "Michelle Williams on 'After the Wedding' ending, equal pay and reveals she's ready for 'Venom 2': 'I'm in'". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ "Venom: Let There Be Carnage". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ^ "Venom: Let There Be Carnage (2021)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Lang, Brent (May 10, 2022). "'I Needed to Stand Up and Deliver': Michelle Williams Goes All in on Spielberg, Pay Equity and the Press". Variety. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ Robey, Tim (May 27, 2022). "Showing Up, review: Michelle Williams unravels in spectacular style". The Independent. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (March 9, 2021). "Steven Spielberg To Direct Untitled Project Loosely Based On His Childhood; Michelle Williams In Talks For Role Inspired By His Mom". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "In 'The Fabelmans,' Steven Spielberg Himself Is the Star". The New York Times. September 11, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ "The Fabelmans". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ "'The Fabelmans' Toronto Review: Steven Spielberg's Cinematic Memoir Becomes Glorious Tribute To Art And Family". September 11, 2022.

- ^ "Golden Globes 2023: Nominations List". Variety. December 12, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "Oscar Nominations 2023: The Full List". Variety. January 24, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c Andreas, Mike Jr. (December 1, 2023). "Michelle Williams On Returning To Work With FX Series 'Dying For Sex' & Why Cinema Was Her "Teacher" As A Teenager — Red Sea Studio". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Shanfeld, Ethan (October 13, 2023). "Michelle Williams Narrating Audiobook of Britney Spears' Memoir: 'I Stand With Britney'". Variety. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ Rhoden-Paul, Andre (October 25, 2023). "Britney Spears memoir: Justin Timberlake impression goes viral". BBC. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Wagner, Erica (January 15, 2018). "The show must go on: Michelle Williams on film, feminism and freedom". Harper's Bazaar. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018.

- ^ Heil, Emily (April 2, 2019). "Cause Celeb: Michelle Williams joins Nancy Pelosi to call for an end to the gender pay gap". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Bennett, Anita (January 5, 2020). "Michelle Williams Advocates For Abortion Rights And Urges Women To Vote in Golden Globes Speech". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Salam, Maya (January 5, 2020). "Women's Rights, Australia Fires and Iran Hang Over Golden Globes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020.

- ^ Setoodeh, Ramin (November 20, 2008). "Michelle Williams tries to move on". Newsweek. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Michelle (January 31, 2011). "10 Questions for Michelle Williams". Time. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Kachka, Boris (December 21, 2016). "Inside the Busy, Brilliant Mind of Michelle Williams". Elle. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017.

- ^ Leonard, Tom (February 19, 2009). "Michelle Williams on picking up the pieces". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018.

- ^ a b O'Malley, Katie (January 10, 2017). "Michelle Williams on playing emotive female characters: 'I try to follow my heart and my gut'". Elle. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018.

- ^ Thomson, David (February 27, 2009). "Michelle Williams". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017.

- ^ Lonergan, Kenneth (September 27, 2016). "Kenneth Lonergan Was 'Totally Unprepared' for Michelle Williams' Dedication to 'Manchester by the Sea'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Travis, Ben; Butcher, Sophie; De Semlyen, Nick; Dyer, James; Nugent, John; Godfrey, Alex; O'Hara, Helen (December 20, 2022). "Empire's 50 Greatest Actors of All Time List, Revealed". Empire. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ Lowe, Victoria (February 25, 2011). "The Best and Worst Oscar Dresses Ever". Cosmopolitan. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "A look back at the most memorable Oscars red carpet dresses of all time". The Daily Telegraph. February 9, 2020. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Michelle Williams For Boy By Band Of Outsiders Spring 2012 Campaign". Flare. February 8, 2012. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017.

- ^ Petrarca, Emilia (July 6, 2015). "Michelle Williams Loves Her Louis Vuitton". W. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018.

- ^ Lindig, Sarah (October 17, 2015). "Watch Michelle Williams Hit the Open Road for Louis Vuitton". Harper's Bazaar. Archived from the original on December 18, 2015.

- ^ "Michelle Williams". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- ^ "These 20 Famous Actors Have Never Won an Oscar". Time. February 27, 2017. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees: Michelle Williams". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018.

External links

[edit]

- 1980 births

- Living people

- People from Kalispell, Montana

- 20th-century American actresses

- 21st-century American actresses

- American child actresses

- Actresses from Brooklyn

- Actresses from Montana

- Actresses from San Diego

- American film actresses

- American people of Norwegian descent

- American stage actresses

- American television actresses

- American women film producers

- Audiobook narrators

- Film producers from California

- Best Musical or Comedy Actress Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Miniseries or Television Movie Actress Golden Globe winners

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Female Lead winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Miniseries or Television Movie Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Lead Actress in a Miniseries or Movie Primetime Emmy Award winners

- People from Boerum Hill, Brooklyn